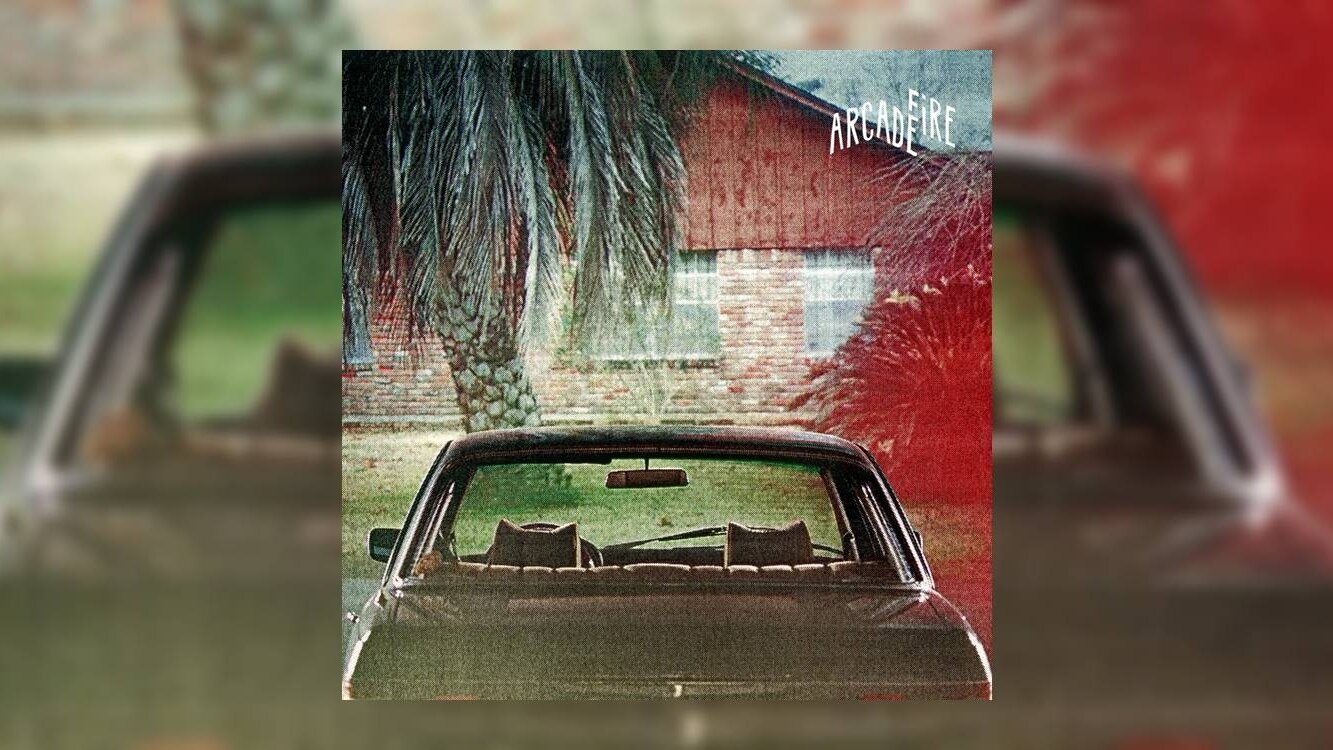

Happy 10th Anniversary to Arcade Fire’s third studio album The Suburbs, originally released August 2, 2010.

During the summer of 1988, the world as I knew it massively changed. My parents sold our house in San Jose, California, and moved us a few towns over. I was 10 years old and saw no reason to vacate this swath of reality I had come to call home. As we emptied cabinets and closets, and tucked belongings into boxes, the accumulation of eight formative years, my mind swam with vague curiosity, but mostly sank under a sad sense of resignation that we were relinquishing our haven to strangers.

No one who’s come and gone since would ever know the life that transpired there—the young couple moving in with their toddler daughter, the son who was born right after and all the many moments between them which the walls bore witness to. No one would see those minutes, days and weeks go by. My childhood, it seemed, was being erased. These imposters would never know it was the home where I grew up—and even if they did, they wouldn’t care.

One night, it was time to say goodbye. My uncle picked my brother and me up (so we’d be out of our parents’ hair on actual moving day). He brought his truck, a special treat, but I still got in begrudgingly. As we drove away into the darkness, we passed our neighbor’s cat and all I could think was I’d never see it again.

The starry-eyed feelings surrounding that house remain enshrined in their own preciously hazy class. I still see so much in my mind and wonder if those experiences are real or just little made-up movies based on stories passed down and photos from albums I’d scoured for hours.

If only there were a way to bottle it all, so everything is clear and nothing is missed, but instead there are more leaks and gaps than facts, and the further we get from it, the more tenuous our grasp, even if we think we still remember it vividly. This prolonged defeat, the inevitable consequence of the passage of time, can send you spiraling if you let it.

And then a band you’d always thought imminently catchy, if not particularly emotive, comes along and releases their third full-length album, bestowing not a bottle, but a spout, unleashing torrents of latent memories, pushing forward faces, conversations and sensations never truly forgotten.

For anyone who grew up in the 1980s and skews even slightly sentimental, Arcade Fire’s The Suburbs is essential listening, an exaltation of nostalgia that celebrates the quiet tribulations and thrills of a childhood lived in a slower time. Exchanging letters with pen pals, driving aimlessly with mix tapes, swinging on playgrounds into oblivion. Somehow, we subsisted on our imaginations, but am I wrong to think we were also more immersed, attuned and present?

Like the previous Arcade Fire LPs, Funeral (2004) and Neon Bible (2007), The Suburbs is a concept album. But, whereas the former two fell into place over time, the latter was approached more intentionally at the outset. Singer and songwriter Win Butler had been living in Montreal for nearly a decade after relocating from the Houston suburbs for college. And life was quickly taking shape. In less than five years, he’d co-founded Arcade Fire with his best friend, Josh Deu; met and married Régine Chassagne, who would become the band’s other principal songwriter; and enjoyed unexpected commercial success. The more he slipped into this new life, the more he felt compelled to revisit his youth before it fell completely out of sight (“They keep erasing all the streets we grew up in”).

The chorus of album opener and title track—one of the first songs written for the record— describes the fear (“Sometimes I can't believe it / I'm moving past the feeling / Sometimes I can't believe it / I'm moving past the feeling again”).

“The Suburbs” also introduces the idea of the “suburban war,” a theme that simmers throughout the album in various facets. The “war” is as much about the trivial external jockeying that takes place among differing cliques and demographics as they tout their juvenile values and stances as it is about the internal strife we face, both then and now.

So much of the suburban adolescence is predicated on escape—deliverance from the bubble (in high school, my friends and I were always quick to interject we were from Shallow Alto, not Palo Alto, in all its placidly vapid perfection). We were intoxicated by the grit and glamor of The City, where real life seemed to happen. Until then, we just had to endure the wait, restless souls on the brink of adventure, culture and magic. But, looking back on our lives as adults, we realize how finite time is and lament how quickly it all goes by (“So, can you understand / Why I want a daughter while I'm still young? / I want to hold her hand / And show her some beauty before this damage is done”). In acknowledging that between childhood and adulthood, we dream of future and past, The Suburbs searches in earnest to make sense of the present.

The two points of view are illumined beautifully in “Modern Man,” one of the record’s dreamier tunes. The rhetoric to our younger self is “Maybe when you're older you will understand / Why you don't feel right / Why you can't sleep at night now.” Meanwhile, the older self is fretting, “Oh, I had a dream I was dreaming / And I feel I'm losing the feeling / Makes me feel like / Like something don't feel right.” Can we ever, pray tell, get the balance right?

Although the impetus for the album stemmed from Butler’s desire to reconnect with his time in Texas, the sixteen tracks were minted in the usual Arcade Fire way, with Win and Régine crafting rough sketches, which they then passed along to the rest of the band—multi-instrumentalists (and Win’s younger brother) Will Butler, Tim Kingsbury and Richard Reed Parry, violinist Sarah Neufeld, drummer Jeremy Gara—often enlisting still other contributors until the collective agreed the songs were fully realized.

Between the recording of Neon Bible and The Suburbs, Will studied electronic music. Its influence here not only gives the album a broader stylistic range than previous works, but also suits its subject, with a synthy ‘80s sound that in itself evokes a certain wistfulness.

In an interview with BBC Radio 1, Win commented, “I think if the record doesn’t sound electronic, then that’s like the greatest compliment…There are songs to me on this record that sound like Depeche Mode mixed with Neil Young and that’s kind of a weird combo. And, if it doesn’t sound weird, then I think that’s a success.”

While surely awakening a bittersweet longing through its musical composition, The Suburbs also succeeds in doing so lyrically. The album is filled with incisive phrasings that demand attention. Perhaps, the greatest testament to its bardic prowess is the soaring, epic “Suburban War,” which stood out to me from my earliest listens and now persists unmatched—my unequivocal favorite Arcade Fire song to date. Echoing threads from preceding tracks and instilling its own shimmering poetry (“Now the cities we live in could be distant stars / And I search for you in every passing car”), “Suburban War” brings it all to heart-shattering climax that I honestly don’t always have the strength to bear. It’s that good, and if you’ve never heard it, I implore you to play it now.

In keeping with the spirit of The Suburbs, when reflecting on his writing process, Butler recalls guidance from his high school years: “I had a teacher at high school who gave me Orwell's short essay on how to write, and the thing I took from it is that you always have to find a specific person doing and thinking specific things in a specific place to illustrate something bigger….That kind of stayed with me: the notion that good writing is like a window pane on the world. Our music may sound big emotionally but that's more to do with the playing, the level of musicianship and the full-on energy. Often, the lyrics are often quite small and focused.”

Whether you hail from the suburbs or not, there’s no denying Arcade Fire’s The Suburbs is a wrenching wander into a bygone chapter. It beats back the superficial ennui of youth, revealing private insular joys—retracing those firsts in life and the seminal grooves in which they registered.

It’s worth noting, shortly after the album’s release, an interactive film entitled The Wilderness Downtown appeared. Featuring the anthemic “We Used to Wait,” the video prompts you to input your childhood address and then takes you there via Google Earth footage (mind you, this was done back in 2010, so the concept was quite novel). While watching, goose bumps formed, as I relived that glory with mounting waves of intensity—that feeling of coming home. It’s so clear, so simple, when we’re kids, and we cling to it, somehow sensing its sublime singularity even in our earliest days.

Home—we attach its meaning to a place and maybe even a time. In fact, it’s one of my best-kept secrets that I wrote my full name in the closet of my childhood bedroom. I figured it was safe there, protected from any scheming painter. And while I still like the genius of it, I now also believe in a more meaningful permanence—the notion that home resides inside me. Yes, that’s the aged mind in all its infinite wisdom.

Note: As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism may earn commissions from purchases of vinyl records, CDs and digital music featured on our site.

LISTEN: