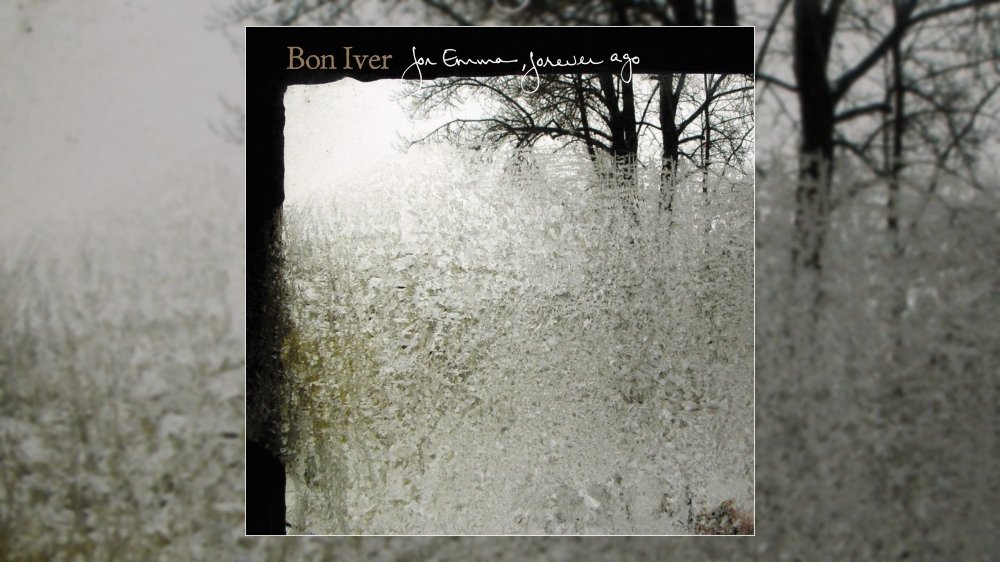

Happy 15th Anniversary to Bon Iver’s debut album For Emma, Forever Ago, originally released independently July 8, 2007 and subsequently via the Jagjaguwar label February 19, 2008.

At first, I thought this was cheesy. I’ll admit it. At a Bon Iver concert in Forest Hills, NY this June, a couple of people in the high seats turned on their phone flashlights and waved them around slowly during “Re: Stacks.” Two lights, on opposite ends of the bowl. “Oh, come on now,” I was thinking.

But then more and more started to appear, and pretty soon, the stadium was all fireflies, waving back and forth. The stage lights still shone brightly on Justin Vernon, and the unintentional imagery was clear: this was a song about heartache, about never being able to fully move on, written ten years ago. And even though Vernon is undoubtedly in a different emotional place now than he was then, singing that song re-isolates him. As the final verse goes: “your love will be safe with me.” He never fully let go.

The difference that night was the lights from the crowd, which enveloped Vernon like a hug. For a moment, everyone saw someone in need and did what they could to bring literal light to him.

There’s a line from the Black Crowes song “And The Band Played On” that encapsulates For Emma, Forever Ago (2007): “the music sounds just like it feels.” This album is a whisper, a collection of songs mumbled over an acoustic guitar, each of which is on the verge of collapse.

“Flume,” the opener, puts up a display of functional indie folk for about two verses before completely falling apart, devolving into a barren, free-time section of scraping and guitar harmonics. It eventually pilots back to a burdened chorus, evoking that Pynchon line: “don’t expect me to ascend wearily out of my melancholia just so everybody else can have their own idea of a good time.” The outro is muted, spent, as if all of the Vernon’s goodwill was wasted on that last chorus, and there’s still thirty-four minutes of the album left.

While For Emma exists in most of our imaginations as an acoustic guitar album, Vernon uses a lot of the compositional tricks that would define Bon Iver’s more complex work (such as 2016’s masterful 22, A Million). On “Blindsided,” for example, the bridge works its way preposterously high in Vernon’s falsetto, and maybe most musicians would drive the bridge home with louder and faster strumming, to crash into the final verse. But instead, Vernon backs off, eases into a gentle electronic effect, and starts the last verse right back at square one. It’s a non-climax that keeps For Emma’s sounds and emotions unique—many other albums sound like the idea of For Emma, but no other album inhabits that same space. This, I think, is what makes it such a stable work.

Lyrically, For Emma is spectral, somehow a combination of a journal and a poem. On “Blindsided,” Vernon straightforwardly confesses that he’s comfortable sitting in his misery, that it takes less courage to do that than it does to try to make something new and move on. But “Lump Sum” opens “Sold my cold knot / a heavy stone / sold my red roses for a venture home,” a verse that feels like it would turn to fog if you reached out to touch it. Sometimes he’s completely direct and sure of what he thinks, sometimes he’s throwing language at the problem in order to turn it into something. In either case, the lyrics serve as another instrument, both containing linguistic and musical meaning (as they do on most Bon Iver works), which just serves to deepen the sense of place on the record.

And now, ten years later it is this version of Bon Iver that feels like it is forever ago. As I was leaving the concert at Forest Hills, I heard someone behind me say “I don’t know. It was a little experimental. I’m a For Emma purist.” I understand that instinct—we got one of the best indie folk albums ever and the guy who started it all decided to never go back in that direction. I fell into that trap too: I didn’t listen to 22, A Million (2016) in the year after it came out because it just seemed too…different. (This was a bad decision.)

But as much as For Emma was about being frozen in time, it was also about moving on—or recognizing that you’re always frozen and always moving on: “But this is not the sound of a new man or a crispy realization.”

Everyone in that stadium knew that the guy on stage still has Emma’s love locked inside of him, even if it’s in a very hard-to-reach place, and that this story starts there. But we also all held out our flashlights, and welcomed and encouraged reinvention and moving along.

The gift of the album is that it can be a place where we can lock away those insecurities and sadnesses, open them when we need them—the first snowfall of the year, a long drive late at night, a cloudy afternoon where it just seems like nothing will get done. But a lot of the time, the record can hold on to those things for us, locking them away and giving us the wherewithal to know when someone else needs that kind of comfort, so we know to shine a light on them.

Enjoyed this article? Read more about Artist here:

Bon Iver (2011) | 22, A Million (2016) | i,i (2019)

LISTEN: