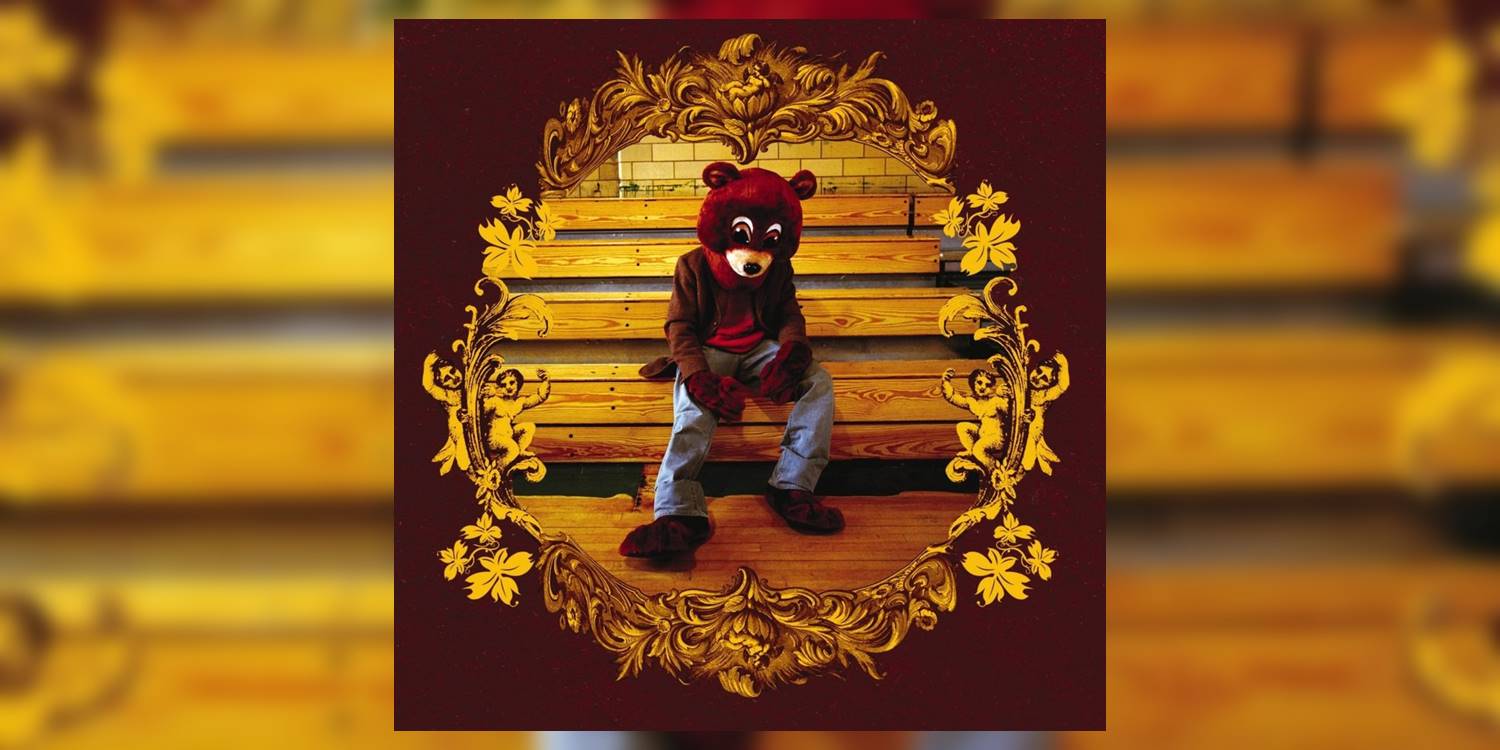

Happy 15th Anniversary to Kanye West’s debut album The College Dropout, originally released February 10, 2004.

Sometimes writing these tributes is hard. Especially when you need to balance who an artist was 15 years ago with what he or she has become, both in terms of their music and personality. With that in mind, I’ll say this: Kanye West has always been an asshole, but at least 15 years ago, he was an asshole who made good music. And one who didn’t share repugnant opinions with anyone who’d print or repeat them.

Regardless, these days listening to Kanye speak can easily remind someone of listening to someone with an obvious chemical imbalance in their brain, ranting from a busy sidewalk when passers-by rush past, trying not to make eye contact. In his role as a Drumf-loving C.H.U.D., he’s made some incredibly ignorant and dangerous statements in the last year or so.

To make matters worse, his music has been largely trash for more than a decade. Aside from the at times brilliant My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy (2010), musically Mr. West has been on the decline since 808s & Heartbreaks (2008). He appeared to hit rock bottom with The Life of Pablo (2016), but further cratered with last year’s Ye (2018). The “promotion” of Ye coincided with embarrassing appearances on TMZ and in the Oval Office, both punctuated by beyond cringe-worthy screeds.

Hence, paying tribute to The College Dropout, West’s first album, is a difficult proposition. Released a decade and a half ago, it was an excellent entry that would mark the beginning of Kanye’s unexpected career as a rapper, where he would reach the heights that few who came before him, and even fewer who came after him, would attain.

But The College Dropout represented more than just a dope album back in early 2004. Though Kanye came off as more brash and confident than most, he recorded material that worked to make him more relatable to the everyday person, touching on themes that many could sympathize with.

Furthermore, he presented himself as the functional bridge between the two commercial and underground sides of hip-hop music. On College Dropout you could hear Jay-Z on a track that ended with a prolonged spoken-word piece and underground hero Mos Def appearing on the same track as Philly-roughneck Freeway. He set out to appeal to those who may spend their time listening to “backpacker” hip-hop, but could still appreciate the artistry and skill of a rapper like Ludacris.

Kanye positions himself as the underdog, a kid who no one believed in who realized his full potential. He rails against his school, his job, and various industry insiders he asserts never thought he was going to make it. This last claim is a little disingenuous, even by his own admission. It’s not that label reps refused to believe in him; they didn’t think he’d be a successful rapper. Many maintained that he should stick to his bread and butter as a producer. By the time College Dropout hit the shelves, Kanye had a proven track record of success behind the boards, starting with independent Chicago artists in the mid ’90s and then gradually transitioning to producing hits for established hip-hop heavyweights and legends like Jay-Z, Talib Kweli, Scarface, Lil Kim, dead prez, and the aforementioned Ludacris.

There’s something to be said for rooting for someone who works to do something no one thinks he can do. Early on, Kanye’s rapping skills were, to be generous, limited. But throughout College Dropout he finds a way to maximize his talents. At its core, College Dropout is about Kanye seeking acceptance. It’s the story of the kid who struggled to be taken seriously, but eventually transformed himself into the “Louis Vuitton Don,” and ended up getting signed to the hottest hip-hop label in the land, co-signed by arguably the genre’s biggest stars.

Another related theme on the album is rising up to conquer adversity. Which is at least partly why the album’s first single “Through the Wire” was such a hit. Famously recorded weeks after he was involved in a serious car accident, he delivered his raps in the studio while his broken jaw was wired shut. Moreover, it showcases Kanye’s production style that made him a sought-after producer and dominated his sound from the late ’90s to the early ’00s. Kanye builds the track around sped-up samples of sections of Chaka Khan’s hit “Through the Fire.”

Kanye was far from the first producer to utilize “chipmunk soul”; RZA had built the production of the early Wu-Tang releases around the production technique in the mid ’90s. However, as sample clearances had become cost prohibitive in the late ’90s and early ’00s, many artists were opting for sample-free production. As Kanye slowly began to amass hits incorporating samples of R&B records from the ’70s, labels began to loosen their purse strings and pay the often-steep costs to sample these records. For what it’s worth, Kanye was instrumental in bringing soul back to mainstream hip-hop releases.

Even back in 2004, Kanye’s public and rapping persona was that of an egotistical braggart. However, 15 years ago there was still a level of respect and empathy that remained beneath the swag. This was especially true on the album’s singles, such as “All Falls Down,” where he grapples with insecurity and consumerism, as he seeks a way to fit it. The Grammy Award winning “Jesus Walks” is one of the few instances where Kanye comes close to downright humility, as the song serves as a celebration of his faith and his dedication to Christianity and walking the righteous path.

“Spaceship” is one of the better songs on College Dropout, as it encapsulates the frustration of those striving to pursue their dreams being caught in dead-end jobs in order to make a living. Kanye bemoans balancing a soul-sucking day job at The GAP with the process of trying to put in work as a producer and artist. GLC and Consequence also contribute solid verses, with the latter reflecting on the embarrassment of being forced back to the realm of the 9-to-5 after briefly gaining recognition as an emcee.

“The New Workout Plan” isn’t the album’s best song, but it’s a preview of things to come for West as a beat-maker. Ostensibly an instruction for women on how to be better groupies, the track pulses along electronically, charging at a fast pace. American Israeli hip-hop violinist Miri Ben-Ari, who’s a frequent guest on the album, adds her unique talents as well. Within the song, you can see the genesis of where West would eventually go with songs like “Stronger” and “Power.”

College Dropout really finds its groove in its back half to final third. “Slow Jamz,” the album’s second single, comes off as a bit of a novelty, with appearances by both Jamie Foxx and Chicago’s Twista (as well as ad-libs by Aisha Tyler), but it still features some of Kanye’s most clever lines.

“Breathe In, Breathe Out” is another of College Dropout’s stronger entries. Kanye explores his duality, positioning himself as “the first n***a with a Benz and a backpack,” but still boasting about his material possessions, even though “I got to apologize to Mos Def and Kweli probably.” Over a horn and guitar samples from Jackie Moore’s “Precious Precious,” Kanye laments, “Always said if I rapped I’d say something significant / But now I’m rappin’ ’bout money, hoes, and rims again.” Though the song is heavy on juvenile humor, it features Kanye using his most varied delivery, rapping, “I blow past low-class n***as with no cash / In the four dash six, bitch you can go ask / So when I go fast, popo just laugh / Right until I run out of gas or ’til I go crash.”

Like “Spaceship,” “School Spirit” presents Kanye at his most bitter, railing against higher education and its lack of connection to real world success. With a sped-up loop of Aretha Franklin’s “Spirit in the Dark,” the song possesses one of the best beats on the album, and is strong enough overall that it isn’t even derailed by the exceedingly pointless skits that both precede and come after it. Just to add, after hearing Kanye’s screeds over the past year or so, it’s clear that the guy probably could use a few more years of higher education.

“Two Words” is an excellent lyrical exhibition featuring guest verses from Mos Def and Freeway. In terms of production, Kanye throws in everything but the kitchen, layering more Miri Ben Air strings and the Harlem Boys Choir over chunks from Mandrill’s “Peace and Love (Amani Na Mapenzi): Movement IV (Encounter).” But the lyrical techniques of Mos and Freeway shine the brightest, as they emphasize two words (or syllables) per line.

The album ends with “Last Call,” which serves as an extended explanation of the reasons behind Kanye’s seemingly massive ego. West explains the necessity of his confidence, rapping, “Now I could let these dream killers kill my self-esteem / Or use my arrogance as the steam to power my dreams / I use it as my gas, so they say that I'm gassed / But without it I’d be last, so I ought to laugh.” And his attitude has helped him seize control of his destiny, as he raps, “I ain’t play the hand I was dealt, I changed my cards / I prayed to the skies and I changed my stars.”

However, the song is best remembered for its nearly nine-minute outro, where Kanye explains the lengthy process that led to him getting signed with Roc-A-Fella Records as a rapper. He begins by describing his first experience work with the label, producing “The Truth” for Beanie Sigel, then the rest of his initial interactions with the imprint’s higher-ups like Hip Hop (Roc-A-Fella’s A&R), Dame Dash, and Jay-Z over the next few years. The inclusion of even the most minute details demonstrates how difficult it was for West to be taken seriously as an emcee, especially considering that it was his aptitude as a producer that got him into the room with these power players.

The outro features more moments of humility by Kanye. Even as he disparages the personnel from various labels who didn’t take him seriously as a rapper, he gives props to guys like Talib Kweli for giving him the best early opportunities as a rapper. He also pays respect to the various A&Rs who did try to champion him to their label heads, their pleas falling on deaf ears. Still, the entire outro serves as an extremely lengthy set-up for Kanye’s last line on the album, “Man, you think we could still get that deal with Roc-A-Fella?” Kanye’s transformation into hip-hop artist was complete, and the rest was history.

Of course, Kanye’s history has been so rocky over the course of his career that he’s long since spent any of the good will he built up during those early years. Many credit the beginning of the fall to his infamous interruption of Taylor Swift’s Video Music Awards acceptance speech in 2009. But in the subsequent decade since that incident, he’s gone from arrogant annoyance that makes good music to delusional rambling jerk possibly suffering from mental illness.

These days, Kanye is mostly a disturbing sideshow act. He resurfaces every few months to stir up shit through his Twitter account or TMZ, only to disappear again just as suddenly. I assume the Kardashian/Jenner family feels the need to be sequestered from him somewhere out of fear he’s going to tarnish their brand and money-making machine.

Kanye certainly remembers what he used to be. The brief “I Love Kanye” on The Life of Pablo indicates that he has at least some level of understanding that not everyone is a fan of what he’s become. I realize that it’s unreasonable to expect West to rap and smoke blunts in front of The GAP, but I imagine he’s still capable of creating music that people can relate to. I would hope so, because becoming so enraptured with your own narcissism and crawling up your own ass on every project has extremely limited shelf life. Here’s hoping that Kanye can again become someone who people can root for, instead of the sad spectacle with little to no self-awareness that he currently is.

LISTEN: