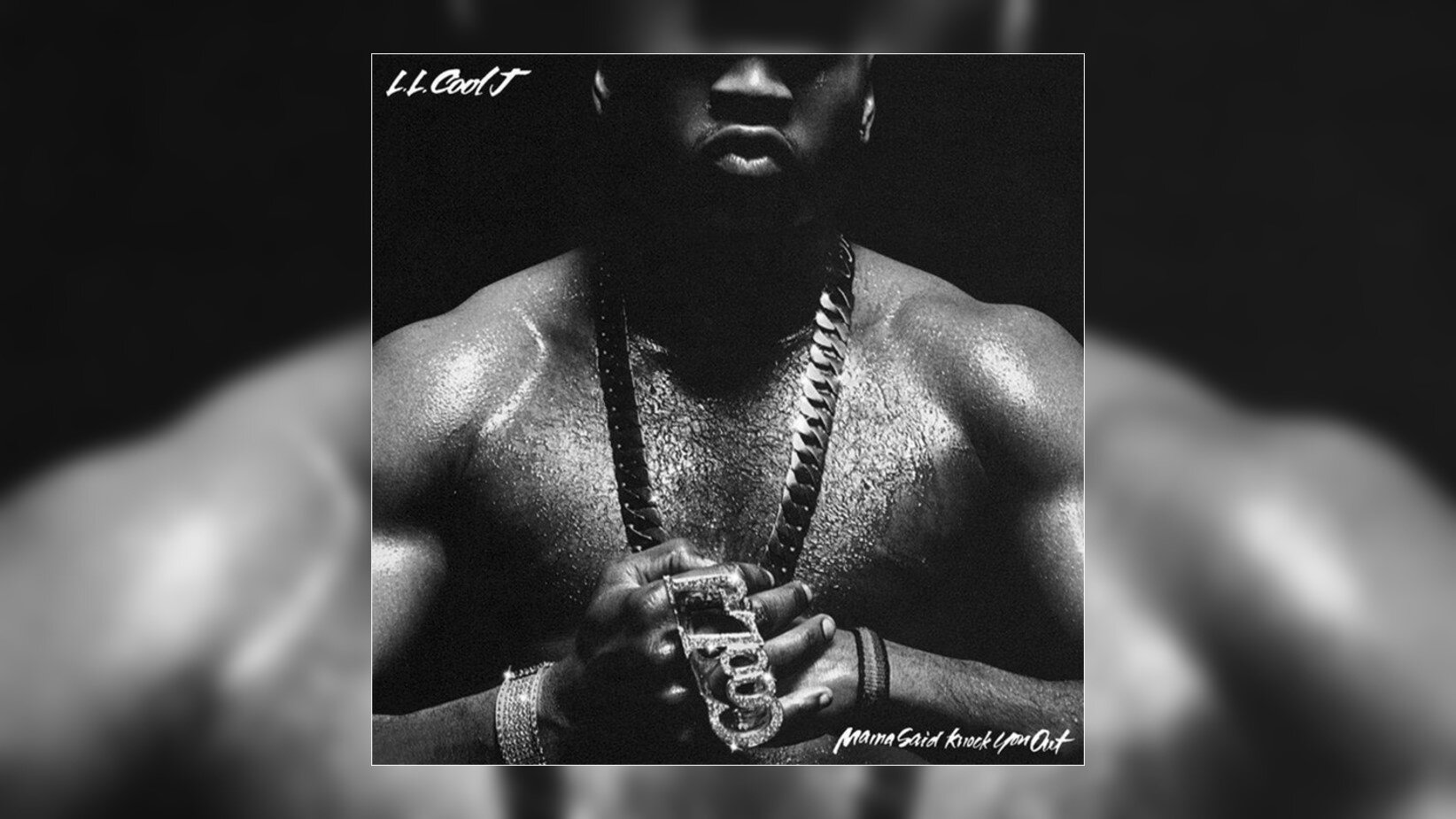

Happy 30th Anniversary to LL Cool J’s fourth studio album Mama Said Knock You Out, originally released September 14, 1990.

I’ve written before about how Mama Said Knock You Out, the fourth album by James “LL Cool J” Smith, will always be considered the definitive hip-hop comeback album. When it was released 30 years ago, it shook the hip-hop landscape like an earthquake. According to the common belief at the time, LL had been left for dead, rejected by critics, his peers, and his audience, who had rejected him a year earlier after his Walking With a Panther (1989) album apparently fizzled. Mama Said Knock You Out set everything right with the universe; it went double platinum and was a creative triumph. LL played to his strengths and created a well-rounded album that didn’t bathe in its excesses.

I wrote extensively about how the artistic failures of Walking With a Panther are greatly overstated. So is its commercial failure. These days, most rappers would kill for a “flop” like Walking With a Panther. The album went platinum and spawned a few of LL’s most memorable songs. While arguably on the bloated side, there’s a lot to like about the long player. However, the issues that many had with the album went beyond the music itself. For some, it was the content, or specifically, the image that LL Cool J presented to the audience, that they found disagreeable.

During the late ’80s, bragging about how you were the best emcee around while being draped in gold and jewels wasn’t enough anymore. Rappers in the limelight were expected to be more socially conscious, in the vein of Public Enemy or Boogie Down Productions. Or, failing that, they were expected to kick vivid descriptions of life on the streets, a la N.W.A. On Walking With a Panther, many thought LL was too ostentatious and egotistical, and thus losing touch with the everyday hip-hop fan. Rock bottom came when he was booed by the crowd while attending a rally protesting the death of Brooklyn youth Yusuf Hawkins.

LL took the critical slights for Walking With a Panther pretty hard and resolved to use them as motivation for recording a new album. In the midst of this, his grandmother encouraged him to “Go out there and knock them out,” which served as the inspiration for the album’s title.

Another integral component to Mama Said’s success is Marley Marl, who produced the album in its entirety. Up to that point, Marley had spent most of his career producing for artists within the Juice Crew camp, one of hip-hop’s first supergroups. But as the late ’80s became the ’90s, many members of the collective had begun producing for their own material, so Marley was ready for new challenges. LL and Marley had previously been on opposite sides of a rap beef, as MC Shan targeted LL on the song “Beat Biter,” accusing him and Rick Rubin of stealing Marley’s beat to make their seminal hit “Rock the Bells.” But by 1990, that rivalry had been forgotten.

LL and Marley first decided to work together when the former visited the latter’s “In Control” radio show on WBLS to promote Walking With a Panther. Marley told LL that while he really enjoyed the album track “Jingling Baby,” he believed he could “fix” it. The remix ended up being a musical tweaking, rather than a full reworking; the final version featured the bassline break from The Grass Roots’ “You and Love Are the Same” and the keyboard intro from Central Line’s “Walking On Sunshine.” LL also re-recorded the vocals in order to give the song a more “laid back vibe.” Def Jam released the remix as the sixth and final single from Panther. With the accompanying video, the remix was a massive success, re-energizing LL’s career just as it appeared to be faltering.

Realizing that they had chemistry together, LL and Marley continued recording material. According to Marley, they’d recorded about eight songs together before someone realized that they had nearly enough material to release an album. At that point, Marley hadn’t even signed a contract with Def Jam agreeing to produce an album for LL. Eventually they put together a 14-song album, which included 11 new tracks and three previously released tracks.

The recording process for Mama Said Knock You Out was often pretty interesting. LL, Marley, and crew would spend the evening in Manhattan clubs like The Tunnel or The Limelight. Eventually, during the small hours of the morning, they would speed back to Marley’s “House of Hits” studio in upstate New York, and record music reflecting the overall vibe of the evening. This process resulted in perhaps the defining album of LL’s career.

The album’s title track is arguably the defining song of LL’s career. The hyper-charged anthem crashes through like a proverbial wrecking ball, unleashing LL as a snarling ball of anger and energy. It’s not a particularly commercially accessible track, as it’s known for its thundering use of James Brown’s “Funky Drummer” break and bellowing chants from Sly and the Family Stone’s “Trip To Your Heart.” And yet the single went gold and the song went on to win Best Rap Solo Performance at the GRAMMY Awards.

The song had its genesis with DJ Bobcat, who, along with the rest of the LA Posse, had helped produce LL’s Bigger and Deffer (1987). Bobcat had put together a couple of earlier versions of the track, which featured vocals from the various Los Angeles-based groups that he was working with, including Menace To Society and The Microphone Mafia. The beat made its way to LL and Marley after Bobcat went to stay in LL’s apartment in Queens during the Mama Said recording sessions. Marley liked the initial skeleton of the beat, but added his own flourishes to it.

The legend goes that LL wasn’t feeling well during the recording session for that particular song. Feeling the effects of copious amounts of Olde English malt liquor that he’d consumed and grappling with potential sickness, Uncle L got irritable with the studio engineer, who kept rewinding the tape too far. So just before the beat came on, he admonished the engineer with a “C’mon, man!” and proceeded to give what’s said to be his most aggressive performance of the night. It was certainly astounding to hear LL, often known for his smooth rhyme techniques, deliver a lyrical lashing that brimmed with full-throated fury.

LL never shied away from exhibitions in pure lyricism, and he contributes a few other legendary entries on Mama Said. But in contrast to the sonic bombardment of the aforementioned title track, these other entries are often minimalist by comparison. He brings his raw rhymes to the stripped-down “Eat ’Em Up L Chill,” flipping “immaculate styles” on top of the drum break from the Five Stairsteps’ “Don’t Change Your Love” and spare guitar licks. “I daze and amaze, my display’s a faze,” he raps. “Every phrase is a maze as Uncle L slays.”

LL takes things even further back to basics on “Farmers Blvd.,” a dedication to the St. Albans, Queens neighborhood where he grew up. He reunites with some of his friends and fellow emcees that he used to kick it with before he signed with Def Jam to record the first proper posse cut on any of LL’s albums. Bomb, Big Money Grip, and Hi C each contribute memorable verses in what appears to be their only appearances on a major label release. If they’ve recorded any other material, I would certainly be amped to hear it.

“Murdergram” is one of LL’s most overlooked tracks, but a bit denser musically. It’s listed as being recorded live at the Rapmania concert, a bi-coastal live simulcast event from both New York’s Apollo Theatre and The Palace in Los Angeles designed to celebrate hip-hop’s 15th anniversary. I didn’t watch the event, and recordings of the performance don’t appear on the concert’s VHS or DVD release. Regardless, LL sounds locked in, dropping a massive single verse over a cacophony of horn squeals and frenetic keyboards. “Ain’t no rivals, ain’t no competition,” he raps. “Punk, I'm beating you into submission / I’m getting busier than ever before / Never more will I slack, Imma keep it real raw.”

LL plays with the perception that he’d with fallen off with Walking With a Panther and takes it to the extreme on “Cheesy Rat Blues.” He envisions and narrates one possible future for himself, where the failure of his album causes his star to fall precipitously. Once there’s no “cash in a flash, bankroll to spare,” all of his friends and women abandon him. “I had to learn in an incredibly fast way when you ain’t got no money they treat you like an ashtray,” he laments. During the third verse, he describes life in poverty, where he’s forced to work menial jobs, shoplift from supermarkets, and clean windshields in hopes of securing small change. Though things clearly never got that bleak for LL, it showed that he had some awareness of the impermanence of fame, and how he had to stay motivated.

A line from “Cheesy Rat” (“Cars ride by with the booming system…”) became the inspiration for the first single of the album. “The Boomin’ System,” one of the greatest hip-hop tracks about blasting music out of your automobile. Recorded during a time when people would spend upwards of a grand to have the livest and loudest car stereo system on the block, LL created the song “strictly for fronting when you're riding around, 12 o’clock night with your windows down.” Musically, it follows the more minimalist vein of other entries on the album, mixing samples of James Brown’s “The Payback” with another usage of the “Funky Drummer” break.

As part of his comeback, LL also decided it was time to settle his hash with some of the various emcees he was feuding with at the time. LL had been involved in many battles since the beginning of his career, but two beefs in particular, against Kool Moe Dee and Ice-T, had been lingering for a few years. “To Da Break of Dawn,” which first appeared a few months earlier on the House Party Soundtrack (1990), was a solid right hook to the jaw of his adversaries.

In a career that features many dis tracks, “To Break of Dawn” is right up there among LL’s most vicious. He uses “immaculate styles” to abuse Moe Dee (“You little burnt up French fry”), MC Hammer (“My old gym teacher ain’t supposed to rap”), and Ice-T (“A brother with a perm deserves to get burned”). The song is among the five or ten best dis songs of all time (a list which also features LL’s “Jack the Ripper” near the top), and essentially ended his battles with Ice-T and Hammer. Things carried on with Moe Dee for a little while longer, as the rapper responded with “Death Blow.”

Of course, it wouldn’t be an LL album if Mama Said didn’t feature songs that appealed to women. As I’ve written before, this is one area where Walking With a Panther went disastrously wrong, as it featured three love ballads that are amongst the worst hip-hop songs of all time. In contrast, the more radio-friendly, “for the ladies” fare on Mama Said are far superior. Part of the success comes from speeding up the tempo; rather than syrupy misbegotten ballads, LL and Marley opted to record mid-tempo jams that would play well in the club.

Of these attempts, “Around the Way Girl,” the second single from the album, is the song with the most pop appeal. As far as “for the ladies” songs go, it’s decent, as LL pens an ode to the hip-hop “girls next door,” chilling out on the neighborhood street corners, with the ability to “break hearts and manipulate minds, or surrender act tender be gentle and kind.” Marley takes elements from the Mary Jane Girls’ “All Night Long” and Keni Burke’s “Rising to the Top,” mixing them together to achieve an almost New Jack Swing feel. The Marley-affiliated R&B crew The Flex provides the vocals on the song’s chorus, making the first of three appearances on the album.

LL has also shown he’s extremely comfortable portraying the smooth player throughout his career. He proves his aptitude in that area again with “Mr. Good Bar.” Uncle L spends the song running game on a beautiful woman at a club, dropping some of his flyest pick-up lines over a sultry groove. The beat remains subtle, even though it combines ESG’s “UFO,” with the guitar squeals of James Brown’s “Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved,” and the backbone of All the People’s “Cramp Your Style.”

LL even adds some social commentary towards the end of Mama Said. On “Illegal Search,” which was released as the B-side to the “Jingling Baby” remix, LL addresses racial profiling by the NYPD, utilizing a mix of humor and sharp observations. The song veers a bit more into New Jack Swing territory than I’d prefer, but it’s still eminently likeable.

He ends the album with “Power of God,” a powerful spiritual entry that was inspired by his own awakening before recording this album. Though ostensibly a song about faith and the power of religion, he encourages his audience to find inspiration to be a better person from whatever source they can. “Get a chapter, and gain some knowledge,” he raps. “If not from the Bible or Koran, get a book from college.”

LL Cool J has remained one of the more resilient legends in hip-hop history. After Mama Said Knock You Out, his career experienced a few more valleys and peaks. He made a few monumental missteps over the next 30 years, but has always found a way to persevere, especially commercially. He’s also kept himself busy through a respectable enough acting career. He’s been the co-lead on NCIS: Los Angeles for more than a decade; it’s an impressive run, but one that’s dwarfed by former rival Ice-T’s 20 years on Law & Order SVU.

No matter what type of questionable musical material LL has released, he’s always found a way to bounce back and maintain his rarified status. He’s learned how to bounce back and give the people what they want, while never overtly pretending to be something that he’s not. It’s doubtful that he would have able to do so without applying the lessons he learned with Mama Said Knock You Out.

LISTEN: