Happy 30th Anniversary to Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Ragged Glory, originally released September 9, 1990.

Neil Young had a rough go of it in the 1980s. After spending his entire solo career with Reprise, he decided to take a chance on an old acquaintance. So he signed with David Geffen’s label in 1982 and immediately started pissing him off by releasing Trans, an album of cold, digital, new wave-leaning songs, most of which were recorded using a vocoder effect. That was followed by the all rockabilly (and all-too-short) Everybody’s Rockin’ (1983) (co-credited with the “Shocking Pinks”), and the straight-up country of Old Ways (1985). These stylized genre exercises caused Geffen to file an unprecedented lawsuit against Young for making albums “unrepresentative” of his music.

To be fair, Young spent much of the ‘80s concentrating on what really mattered, taking care of his sons, both of whom had been diagnosed with cerebral palsy. At the time, he felt he was making music without putting his soul into it, reserving that part of himself for his family instead. Eventually, however, he and his soul found their way back to the music. He realized he had enough of it to spread around.

The lawsuit was settled out of court in 1986 and Young went on to release two more albums for Geffen to fulfill his contract (Landing On Water and 1987’s Life with Crazy Horse), before moving back to the familiar comfort of his first label, Reprise. Once back home, he released another genre exercise, this one of more of an uptown blues/swing band project (dubbed the “Bluenotes”) complete with a full horn section called This Note’s For You (1988). (The album was most notable for the title track, whose video was initially banned by MTV, only to end up winning the video of the year honor at their Video Music Awards the following year.)

After surprisingly reuniting with David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Graham Nash for the unremarkable American Dream album late in ‘88, Young followed This Note’s For You with the true return-to-form of Freedom (1989) the following year, which included a new Young classic, “Rockin’ In The Free World.” With acoustic and electric versions of the song bookending the album a la Rust Never Sleeps (1979), it drove home the point that Neil Young, and his soul, were back in the game.

After hitting the road in support of Freedom and participating in a quick benefit tour with Crosby, Stills, and Nash, Young retreated to his Broken Arrow Ranch in April of 1990 with Frank “Poncho” Sampedro, Billy Talbot, and Ralph Molina. He had weathered a decade of lawsuits and uncertain paths and had found his footing again with a critically acclaimed album and tour, now it was time to call in the Horse.

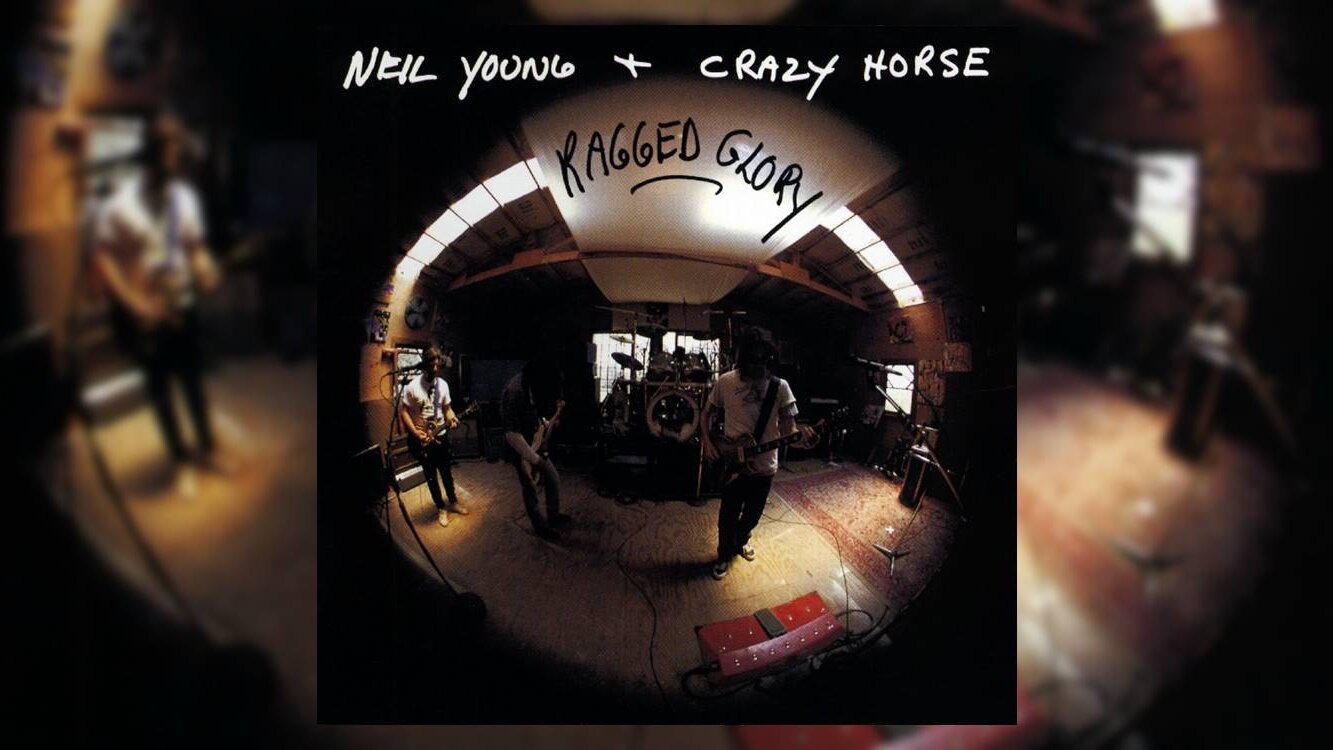

Neil Young uses Crazy Horse as his vehicle for sonic exploration. During their lengthy jams, they tap into a rarified primal mode of creativity. That occurred when they convened at Broken Arrow, Young’s ranch in Redwood City, California that he’s occupied since 1970, to jam on a set of songs inside his plywood barn. That set of songs ended up becoming two sets per day for two weeks. No song was repeated during the sessions so as to keep the spontaneity flowing.

Engineer John Hanlon was instructed by producer David Briggs to keep an eye on Young and to be ready to record in case he picked up a guitar or sat down at the piano because chances are he’d want to listen back to, and most likely use the first take, no matter how many times the band ran through it.

Young’s PA system was set up in the barn as he and Crazy Horse played all the songs live from the floor. Mics leaked. Guitars squalled and fed back. Amps buzzed. Songs jammed on and on. The perfectly named result, Ragged Glory, is one of Young and Crazy Horse’s greatest achievements in their long and storied careers.

Its first two songs, “Country Home” and “White Line,” date back to the ‘70s, with the latter recently surfacing in its earlier form on Young’s long-awaited release of Homegrown. On Ragged Glory, however, it’s given the Crazy Horse treatment. Molina’s insistent beat trots along as Sampedro, Young, and Talbot all gallop down the open road. They also resurrect a garage rock classic in Don & Dewey’s “Farmer John” by way of the Premiers, but Crazy Horse slows the beat down to a sludge-filled stomp as it plods along under the sinister crunch of Young and Sampedro’s Les Pauls.

In the grand tradition of “Welfare Mothers,” “F*!#In’ Up” answers each line with the half-question, “Why do I?” until the chorus completes the query, “Why do I keep fuckin’ up?” Powered by its insistent riff and brutal volume, it eventually became a minor anthem of Gen-Xers that came of age during the height of the Seattle scene.

Speaking of Seattle, recorded a year and a half before the release of both Pearl Jam’s Ten (1991) and Nirvana’s Nevermind (1991), it shouldn’t go unmentioned that Ragged Glory played no small part in Young being christened the “godfather of grunge,” with Pearl Jam later covering both “F*!#In’ Up” and the Freedom track “Rockin’ In The Free World” extensively live and Kurt Cobain famously quoting Young’s lyrics from “Hey Hey My My” in his suicide note (which led to Young dedicating the next Crazy Horse project, 1994’s brilliant and harrowing Sleeps With Angels, to Cobain).

“Mansion On The Hill,” with its sunny vision of peace, love, and psychedelic music in the air, was Ragged Glory’s first single. Its theme led the way to the album’s two extended jams, “Love To Burn” and “Love and Only Love,” both of which take Young and the Horse into that area of deep sonic exploration while Young’s guitar squalls through the murk. The past is addressed directly on the Bob Dylan/“My Back Pages” homage, “Days That Used To Be,” which includes some of the most poignant lyrics on the album.

Ragged Glory concludes with “Mother Earth (Natural Anthem),” recorded live at the Hoosier Dome in Indianapolis. Young’s heavily distorted Les Paul strums bare chords throughout as he sings out a gentle prayer for the song’s subject. (He would unveil a similar arrangement to great effect for a version of Dylan’s “Blowin’ In The Wind” on the tour that followed, a recording of which ended up on the live set Weld the following year.)

In the thirty years since the release of Ragged Glory, Young has let the Horse out of the stable here and there to run wild on record and on tour: Sleeps With Angels, Broken Arrow (1996), Greendale (2003), Americana (2012), Psychedelic Pill (2012), and most recently, Colorado (2019) (with longtime collaborator Nils Lofgren filling in for Poncho).

Although some since have been more successful than others, Ragged Glory’s place is secure in the Crazy Horse canon alongside the classics Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere (1969), Zuma (1975), and Rust Never Sleeps. Young has made timeless music with many other collectives and groups, no doubt, and while his recent work with Lukas Nelson’s group the Promise of the Real has yielded some interesting moments, it can’t replace or come anywhere near the power and ragged glory of a Horse in full stride.

Note: As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism may earn commissions from purchases of vinyl records, CDs and digital music featured on our site.

LISTEN: