Happy 35th Anniversary to Prince’s ninth studio album Sign O’ The Times, originally released in the UK March 30, 1987 and in the US March 31, 1987.

In days gone by, before the advent of radar, GPS and all the trappings of modern technology, people all over the globe dared to set sail upon oceans and seas with no idea of what lay ahead. Their curiosity overcame the tremulous fear that lurked within them at the prospect of sailing into the unknown, without any of the technological devices we use today. Instead, they placed their trust in the natural world to guide them to far-off places and return home safely. In the northern hemisphere, the most important tool was the north star, Polaris. Unerring and never shifting, it gave voyagers a fixed point to navigate within a sky that otherwise shifted from hour to hour. A constant that guided and comforted in equal measure.

My musical “Polaris” is Prince’s incredible 1987 album Sign O’ The Times—just as those intrepid voyagers stepped into the unknown world beyond their immediate locale with Polaris to guide them and offer certainty in a world shorn of it, so SOTT does the same job for me in navigating life. Its staggering scope and dazzling array of musical styles and subject matters bookends a time before rap truly took hold of pop music and smacked the shit out of it, making it a full stop in the development of 20th Century music. Taking elements of jazz, blues, soul, funk and rock & roll, it is the culmination of 60 years of musical development in one immaculately produced package.

Despite the certainty and unwavering position it occupies for me, the album itself was born out of the precise opposite of those feelings in the world of Prince Rogers Nelson. To write about any Prince album requires a degree of untangling due to his prolific output and his habit of locking songs away for later consumption—there was rarely, if ever, a straightforward lineage of songs written, recorded and released as albums. With SOTT though, the entanglement was not just due to his artistic foibles but also his personal relationships with those around him.

Three enormous upheavals led to the creation of SOTT. First, there was the breakdown and eventual dissolution of the relationship between Prince and The Revolution. Secondly, there was the tumultuous, longstanding intimate relationship between Prince and Susannah Melvoin reaching a point of no return. And finally, an ego gravely wounded by the comparative failure of Parade (1986) and the accompanying film Under The Cherry Moon.

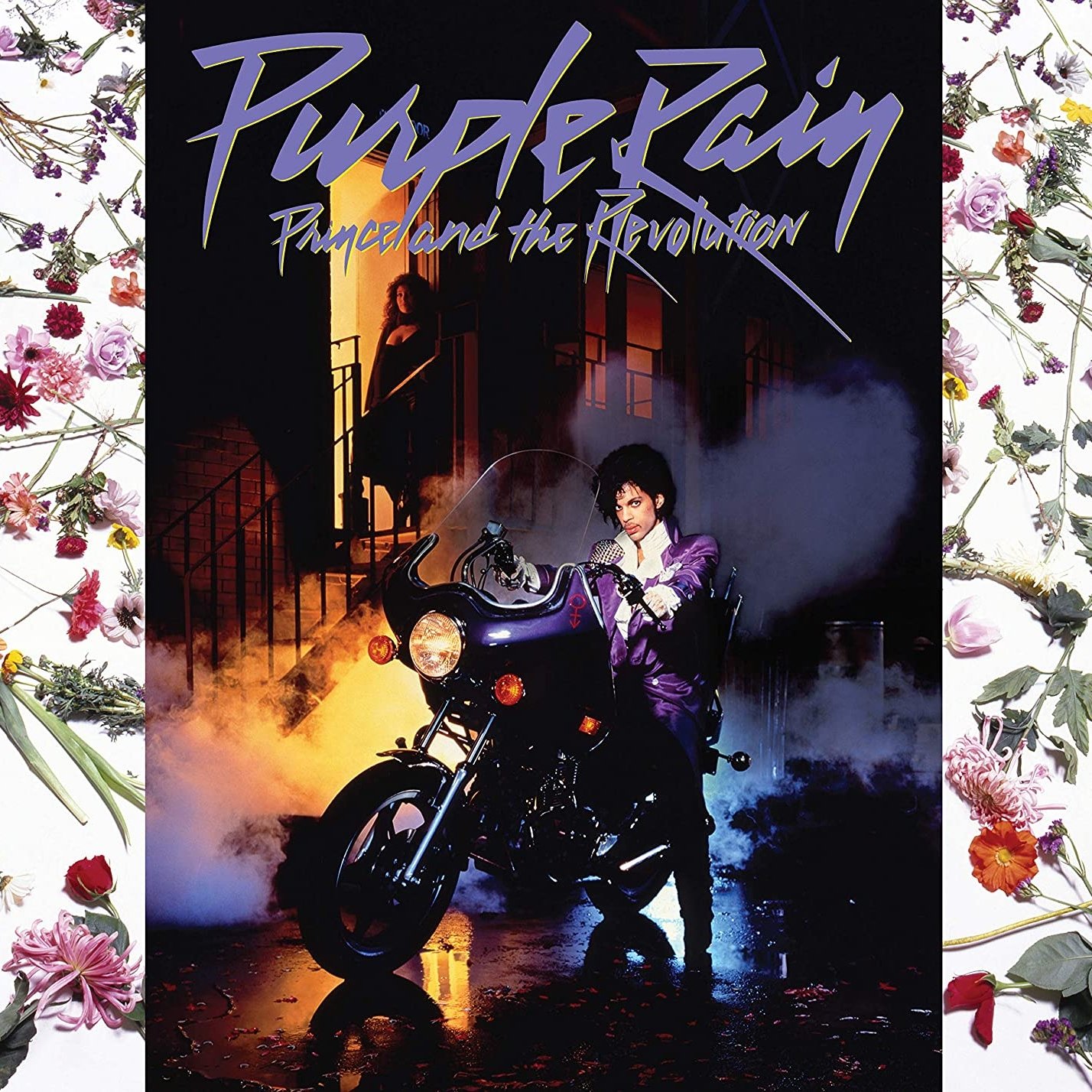

Although Purple Rain’s monstrous, globe-straddling success had introduced The Revolution to the wider world as Prince’s band, some of the group’s members had been around for years in one way or another. Brown Mark, Bobby Z, Dr Fink, Wendy Melvoin and Lisa Coleman were a key part of the success of Purple Rain (1984) and the continued whirlwind of creativity that followed it. This intense period saw the interpersonal relationships between bandmembers become the most important ones in Prince’s life—spending almost every (waking) minute of every day together for months on end could only end that way. However, despite the amazing musical symbiosis that laced 1999 (1982), Purple Rain, Around The World In A Day (1985) and Parade with such unbridled and successful artistry, the dynamic of boss and employees was never far from showing its face.

Watch the Official Videos:

If that dynamic was at play, then as sure as night follows day, money disputes arose—rumblings about payments owed were aired and other financial grievances simmered. As the Princely juggernaut rolled onwards generating income at a staggering rate, the Revolution were only being paid $800 a week while being told to shun any other work and be available at a moment’s notice to drop their lives and run to Prince’s side (should they ever have left it) to record or perform.

A request from Wendy, Lisa and Bobby Z for contracts to assure the group of their (fair) share of what was coming in was taken as a slap in the face by Prince, as Wendy Melvoin explained to MOJO magazine in 2018: “We wanted to be able to work with Prince forever; we just wanted to draw up some contracts, and he took it as an assault on him. He wigged out. He thought it meant we didn’t love him.” “Love or $”, it seemed, was not just the B-side to “Kiss.”

At the same time that The Revolution grew tired of being “the help,” Wendy watched her twin sister Susannah get jerked about by a man who fled from showing his true self and any signs of vulnerability and true intimacy—the man who was also Susannah’s “boss.” Susannah had been in a relationship with Prince for a large part of the mid 1980s and, like most relationships, there were ups and downs. But the strain on Wendy seeing her twin sister go through tough times with Prince must have been tremendous and difficult to untangle from her feelings around the band’s desire for contractual commitments from him. By the end of 1986, Susannah had finally reached the end of the road and finished the relationship with a heartbroken Prince.

All the relationships in his life were in flux with his foundations crumbling around him, but there was another burden—the seismic shock of abject failure for Under The Cherry Moon (the film that accompanied Parade) that had been sent coursing through his ego. No Oscars this time around—just derision and underwhelming public apathy. He seemed to know why things hadn’t panned out as he’d hoped in conversation with Barney Hoskyns for his book Imp Of The Perverse: “Parade was a disaster. Apart from ‘Kiss,’ there’s nothing on it I’m particularly proud of . . . I think half the problem with Parade was that I recorded it too soon after Around The World In A Day and I just didn’t have enough good material ready. I’m never going to make that mistake again.”

This perfect storm of personal and professional relationship turmoil and a career that seemed to be dwindling laid a new set of foundations for Prince to create a unique and daring response. Susan Rogers summarized the motivation for SOTT in Duane Tudahl’s staggeringly fabulous book Prince And The Parade & Sign O’ The Times Era Studio Sessions 1985 and 1986 as follows: “His childhood created Purple Rain, the pressure of his life created Purple Rain, but the pressure of legacy created Sign O’ The Times.”

His response to being vulnerable at the loss of those closest to him was to retreat to the person he trusted the most—himself. A well-used survival tactic in his formative years, it saw him fire The Revolution in September 1986 and return to the isolation and emotional safety that home brought him. As Bob Cavallo (his manager at the time) reflected with Jon Bream in the Star Tribune in April 2019, “He started to not believe in anyone but himself.”

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Prince:

However much The Revolution’s demise was mourned by fans, it is clear from SOTT’s impact and legacy that the trust he had in himself was well placed. It is also clear from the 2020 release of the Super Deluxe Edition of the album that he followed through on the promise of never being short of quality material to choose from. The wrangling with Warner Brothers about releasing much longer albums during this time in the shape of the planned Crystal Ball and Dream Factory albums further reinforced the entrenched siege mentality he felt and forced him further inward.

Those wrangles done, he finalized the album’s contents and sequence on December 23, 1986 and it was sheer perfection. Where previous track lists lacked a certain gravitas, the titular single gave the kickoff that no-one could have predicted—a socially conscious, state-of-the-world-today diatribe. But beyond the impeccable guitar work, militaristic beat and critique, it offers the first example of a masterful array of opening lines (“In France a skinny man died of a big disease with a little name”) that spans the immersive story telling of the perfect “The Ballad Of Dorothy Parker” (“Dorothy was a waitress on the promenade / she worked the night shift”) to the casually disarming “Strange Relationship” opener (“I guess you know me well, I don’t like winter / but I seem to get a kick out of doing you cold”).

In lines like these, he demonstrates an uncanny ability to paint pictures that immediately engage the listener and foreshadow perfectly the tone and subject matter of the song. Those tones and subject matters vary enormously over the double album and therein lies its appeal to me. Not content with one expression of the artist, it takes in the sparse, obsessive sexual desire of “It,” the coquettish swagger of “Hot Thing,” the whimsical gem (with a definite Princely edge) “Starfish And Coffee” and the romantic grace of “Forever In My Life.”

The musical styles come thick and fast too—the monumental funk of “Housequake,” the pop-perfection of “U Got The Look” and the sacred, seismic rock of “The Cross” all sit side by side with ease. That it works is testament to the precision of the sequence of the album. Counterpoints sit side-by-side throughout, bringing balance to the whole. Following the epochal social critique of the title track with the irrepressible exuberance of “Play In The Sunshine” is a prime example of this.

One of the other things to love about the album is the number of happy accidents that litter the recording process. “The Ballad Of Dorothy Parker,” “Forever In My Life” and “If I Was Your Girlfriend” all have features that were unplanned for and remained in the mix as they sounded so good. As Prince’s career progressed, it always seemed that there was no room for mistakes as his work became more and more polished to the point of being clinically antiseptic (to me, at least).

The thing that has always separated Prince from other artists in my heart is that no one else has created as many moments in their music that make the hairs on the back of my neck stand up. No one created as many moments when I need to stop everything I’m doing and bask in the glory of the recorded brilliance and this album is chock full of the moments or passages of music that elicit those primal responses.

There is the dramatic funkiness of the guitar on the title track that stops me dead. The hushed reverence of “Dorothy Parker was cool” just after two minutes into the impeccable Sly Stone inspired groove. The driven to sexual frenzy of the vocal delivery on “It.” The quivering fragility of the intimate ending of “If I Was Your Girlfriend” and the pounding of the drums as the climax of “The Cross” rumbles into place two-and-a-half minutes in.

But one song is filled to the brim with those spine-tingling moments over the course of its six-and-a-half-minute duration. Beautifully poised at the end of the album, bookending the power of the title track, is the greatest ballad of all time and one of my favorite songs of all time. “Adore” builds slowly toward a peak that is so beautiful, it must be the result of divine intervention. A throng of angelic Prince voices combine to create a celestial choir of harmonic rapture, increasing in scope and volume until a positively orgasmic moment at its towering peak. Whenever I listen to it, I gradually increase the volume of playback, heightening the crescendo to levels of blissful nirvana unheard elsewhere. It stuns me with its power and glory each and every time.

Perhaps the most powerful thing about Sign O’ The Times is that it transcends my emotions in a way other albums don’t. Whether I’m happy or sad, it is a friend to lean on and be centered by. It soothes my soul, ignites my passion and thrills at every turn. It is also the album that I judge all others by—the highest benchmark of quality I know, against which all else pales.

Despite the tumult of his life at this time, the truth of his sadness never came out entirely—his fear of vulnerability saw to that. But that was part of his allure—he was an enigma who never entirely let his guard down. Even at the end, we never really knew him.

LISTEN: