Happy 30th Anniversary to Radiohead’s debut album Pablo Honey, originally released February 22, 1993.

Every summer, my brother and I would lounge around the rec room at my grandparents’ house in Minnesota, watching hours upon hours of MTV, trying to catch up on what we had missed during our “normal” teenage lives the rest of the year on an American army base in Germany. The first time I heard Radiohead’s “Creep,” though, we were watching on the little TV in my grandma’s kitchen, eating bowls of her homemade rice pudding. It was the summer of ’93, and I still remember the scene because my dad, who usually didn’t care about anything on MTV, came in to see what the song was. And then we all sat slack-jawed, marveling at what we were hearing.

On the surface, “Creep” recycled the bored, angry alienation Nirvana was already doing so well—“I feel stupid and contagious” and, more to the point, “I’m a negative creep and I’m stoned.” And yet this song had many more layers to it. On the one hand, it was truly creepy, embodying a cold, steely stalker quality that made me shiver in the AC. On the other hand, there was a pulsing, disembodied warmth to it, as Thom Yorke described an angel with luminous skin, floating like a feather through a beautiful world. And then there was Yorke’s own extreme vulnerability, anger replaced with sad pseudo-irony as he sings like a seraph himself, “I’m a creep, I’m a weirdo / What the hell am I doing here? / I don’t belong here.” I loved its wistful bygone waltz, and then the raucous thunderbolt ch-chunk of Jonny Greenwood’s guitar. “Wow,” my dad said, when the song was over. My brother and I nodded in unison.

“Creep” almost didn’t make it as a single. And when it finally did, it almost relegated Radiohead to one-hit wonder status and broke up the band. But first things first. While Radiohead were recording Pablo Honey at Chipping Norton Studios in their native Oxford, they rehearsed “Creep,” a song they considered a throwaway. Their producers recorded it and their label, EMI, went nuts for it, strongly encouraging the band to make it a single. Although it was released as Pablo Honey’s lead single in September 1992, “Creep” received very little airplay. Then, in February 1993, Pablo Honey itself was released to very little fanfare. And then, out of nowhere, “Creep” became an unlikely hit in Israel when DJ Yoav Kutner began putting it into heavy rotation on his radio show. That spring, Radiohead traveled to Tel Aviv to play their first overseas show, and around the same time, “Creep” began receiving airplay on U.S. radio stations, climbing quickly to # 2 on the Modern Rock chart.

By June of 1993, as Radiohead began their first American tour, the music video for “Creep” had begun its constant rotation on MTV. And so my brother and I actually hadn’t missed out on much—that summer, we were catching “Creep,” and Radiohead, in all its (American) freshness. In July, Radiohead even gave an infamous performance of “Creep” and another single, “Anyone Can Play Guitar,” live on MTV’s Beach House, which ended with Yorke diving into the pool while holding a live microphone and almost electrocuting himself. (My brother and I missed that one, because we thought Beach House was lame).

Finally, after a summer of rabid American fandom, the UK was the last to latch onto “Creep,” with the single reaching #7 on the UK Singles Chart that September, but only after EMI had re-released it in the band’s home country. That month, Radiohead performed their hit on Britain’s Top Of The Pops. It was an honor the band likely never imagined when they first began practicing in the music room at Abingdon School, mostly just to escape boredom and bullying.

In 1968, Thom Yorke was born with his left eye sealed shut. The doctors determined that the eye was paralyzed, and that his condition seemed to be permanent. The Yorkes took their son to a specialist, and he ended up undergoing five operations prior to his sixth birthday. The operations had a positive effect—Yorke was able to see with both eyes—but his left eye ended up drooping slightly lower than the right one. Children can be horrible little assholes, and Yorke was taunted by the other boys at the various schools he attended throughout grade school (his father’s job as an equipment supplier had the family moving frequently). “There’s a pervading sense of loneliness I’ve had since the day I was born,” Yorke said. “Maybe a lot of other people feel the same way, but I’m not about to run up and down the street asking everybody if they’re as lonely as I am. I’d probably get locked up.”

For his eighth birthday, Yorke’s parents gifted him a guitar. At age 10, he formed his first band, and by 11 he had written his first song, a little ditty about the atomic bomb called “Mushroom Cloud.” At the beginning of the ’80s, he enrolled in the all-boys Abingdon School in Oxford, where he became friends with bassist Colin Greenwood, who also suffered from taunting and self-consciousness over his appearance. They also both loved outrageous outfits (it was the heyday of the New Romantics, after all). “We always ended up at the same parties,” Yorke recalled. “He’d be wearing a beret and a catsuit, or something pretty fucking weird, and I’d be in a frilly blouse and crushed velvet dinner suit and we’d pass around the Joy Division records.”

The two formed a punk band called TNT, and then abandoned it to form another project with fellow student and guitarist Ed O’Brien. They added drummer Phil Selway to their ranks, and then brought in Colin’s younger brother Jonny, who had been aching to be a part of the band. At first, Jonny was brought on to replace a keyboard player who hadn’t worked out because he played too loudly. “And so when I got the chance to play with them, the first thing I did was make sure my keyboard was turned off,” Greenwood recounts. “I must have done months of rehearsals with them with this keyboard, and they didn’t know that I’d already turned it off.” (Of course, he would eventually become the band’s third guitarist, and actual keyboardist.) The band christened themselves On A Friday, for the simple reason that that’s when they’d rehearse.

Although the band were serious about rehearsing while they were still in high school, every member decided to attend university. Still, they made the band a priority while away, writing new songs and practicing whenever possible. During that time, Jonny progressed from being a fringe member to becoming Yorke’s main songwriting partner. Then, after university, the band all moved back to Oxford and into a shared house. “At first it was quite a nice house, but we turned it into a complete fucking hole,” Yorke remembers.

On A Friday began playing pubs around Oxford, and soon a rough demo they created attracted the attention of Chris Hufford, who owned a recording studio called the Courtyard. Hufford recorded a better demo for the band, nicknamed Manic Hedgehog (after a local record store that agreed to sell the tape). Then, through a lucky break, Manic Hedgehog got into the hands of an A&R guy for Parlophone, a subsidiary of EMI. Soon, the band were signed. From the start, however, EMI made no secret that they thought the name On A Friday was cheesy. The band found their new name on the Talking Heads’ album True Stories, which featured the song “Radio Head.” “It’s about the way you take information in, the way you respond to the environment you’re put in,” Yorke said of the name. “It’s very much about the passive acceptance of your environment.”

The newly minted Radiohead recorded an EP, Drill, and then, after a UK tour, turned their attention to their debut album. Chris Hufford retired his producer duties to manage the band, and around the same time, Paul Q. Kolderie and Sean Slade, who worked at Boston’s Fort Apache recording studio, were in the UK searching for new business. They liked what they heard on Radiohead’s other recordings, and the band were thrilled at the prospect of working with the duo (they certainly liked the fact that Kolderie had engineered the Pixies’ Come On Pilgrim). During the process, Kolderie and Slade guided a band who were very inexperienced. “When they started, they didn’t know how to work in a studio,” Kolderie said. “They were a baby band. We had to show them that you can’t let your desire for being Pink Floyd bog you down. You have to finish.”

And finish they did, with Radiohead christening the freshly pressed album Pablo Honey. The band owned a bootleg of the Jerky Boys’ prank calls, and a sketch they found particularly hilarious was where one of the Jerky Boys pretends to be the victim’s mother, who moans weakly, “Pablo, honey? Please come to Florida.” “‘Pablo Honey’ was appropriate for us, being all mothers’ boys,” Yorke joked.

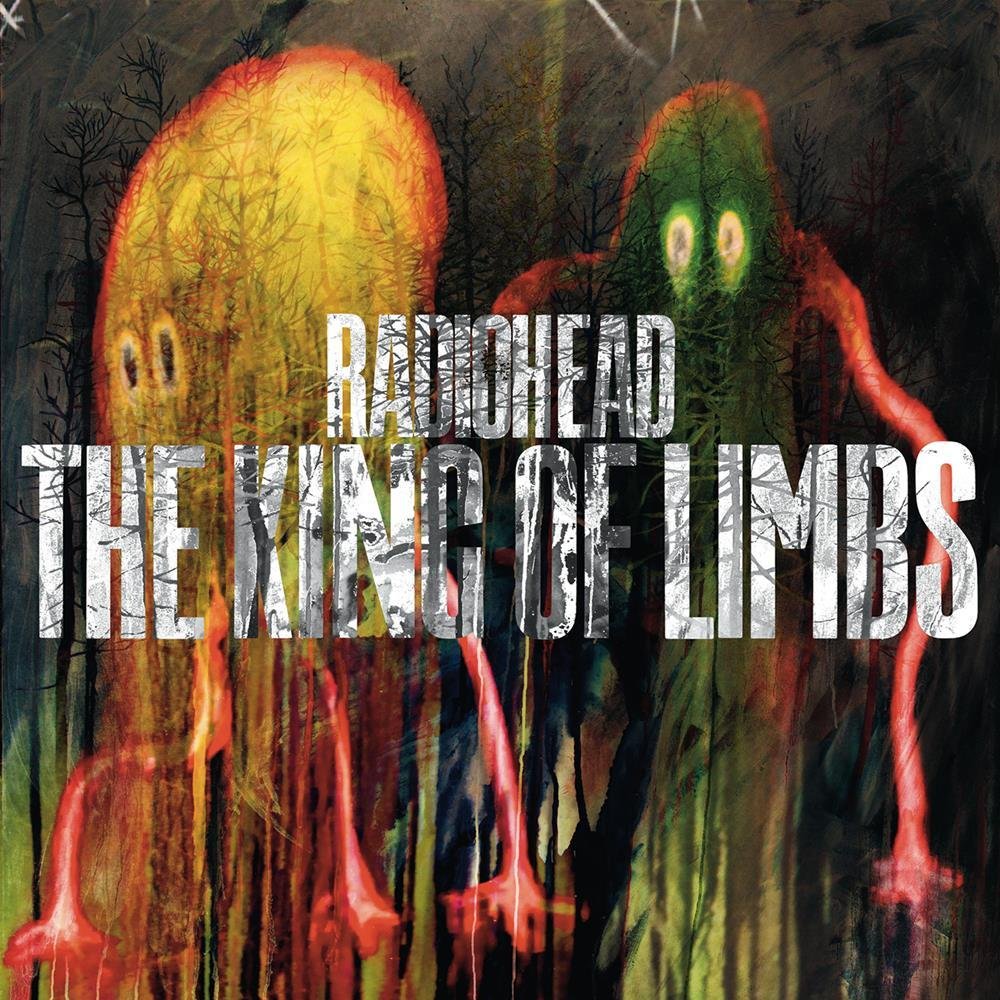

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Radiohead:

Pablo Honey isn’t a masterpiece, but it’s an enjoyable work that contains the rough clay the band would eventually use to construct The Bends (1995), as well as their magnum opus OK Computer (1997). Pablo Honey ended up in frequent rotation on my bedroom stereo and, even then in ’93, I was proud to call myself a Radiohead fan. I’d even hatch a plan to see them play live the following year, but first I had to pass math class.

Pablo Honey kicks off with “You,” which starts out shimmery and then crashes and wails. The guitars form gorgeous layers on this song, Yorke’s voice is slinking and sensual, and it’s a respectable, impression-making opener. “Creep” follows, a much more conventionally structured song than the preceding one, save for its stuttering guitar thunder that Jonny Greenwood added because he hated the song’s serene intro. “I didn’t like it. It stayed quiet,” he said. “So I hit the guitar hard—really hard.” The band loved it, and they ended up nicknaming it “The Noise.”

Next up is the rocker “How Do You?,” a little bit whiny and Sex Pistols-esque, and not my personal favorite, though there’s artful arrangement of the guitars and some interesting Krautrock-inspired piano and drums. In a stylish multimedia flourish, the band also include the nearly-muted Jerky Boys’ “Pablo Honey” call as part of the breakdown at the end. “Stop Whispering,” though a more basic track, features soaring Bono-like vocals, and a building-and-dissolving layering of the guitars for an overall mood of exuberance.

The folky, acoustic “Thinking About You” is Colin and Jonny Greenwood’s mom’s favorite song, which they find hilarious because the track is about wanking. (Embarrassingly, they had to inform her.) But considering that the members of Radiohead went to an all-boys’ school, masturbation was a normal part of life, and so they decided to write a song about it. The poppy, catchy, distortion-studded “Anyone Can Play Guitar” is simultaneously an ode to the power of the electric guitar, and an ironic scoffing at its transformative power. (In an avant-garde gesture, Jonny Greenwood played his guitar with a paintbrush during the recording.) “Ripcord” is another track of poppy exuberance, with Yorke’s voice flitting in and out of the playful guitars like an exotic bird.

“Vegetable” is a sad country-infused ballad about an imploding relationship and domestic violence—“I never wanted any broken bones / Scarred face, no home.” The lyrics are harrowing, but the fuzzy Pixies-esque guitars make you guiltily bop your head. “Prove Yourself” is a bit repetitive and feels more like filler than anything else, though it’s not a horrible song (just a slightly boring one). “I Can’t” sounds like a lot of early-2000s indie pop, and it was the first track on the Manic Hedgehog demo. It’s a pleasant jangle, and isn’t bad as a near-end track. “Lurgee,” named for a hazily defined loneliness, combines sadness with sunniness in a way that Radiohead always does incredibly well, and it’s a hypnotic, lazily flowing track that doesn’t necessarily suffer from its lack of well-defined structure. The album ends with “Blow Out,” a jazzy number with a Latin-infused intro that then morphs into a noisy second half with Yorke wailing over the fuzz.

Over the next year, Radiohead toured Pablo Honey extensively and became so disillusioned with the crowds’ desire to hear “Creep” that they nearly broke up the band. "It's like it's not our song anymore,” Yorke said. “When we play it, it feels like we're doing a cover." Fortunately, though, they stuck together and kept touring, using the performances to tighten their skills and write new material for their next album.

For months in early 1994, my best friend Nikki and I began gabbing endlessly about Rock Am Ring, a music festival a few hours away that would feature The Breeders, Smashing Pumpkins, Rage Against The Machine, and Radiohead. I begged my mom to drive us (actually, because it was a three-day festival, it was also going to involve camping in our van overnight) and she agreed, as long as I raised my math grade. My brother and I were told that we could each bring a friend, and naturally I chose Nikki. The problem was, Nikki was also in my math class. It was a math class specifically for fuckups, which we had wound up in after failing Algebra the year prior due to too much socializing (with each other). Sadly, we were already up to our usual shenanigans, being loud and talking too much, and not doing a whole lot of math. But somehow we pulled it together, and we pulled off that damn trip to Rock Am Ring.

The morning of the festival, we drove onto the residential part of the army base to pick up my brother’s friend. My brother was still in middle school, and so I hadn’t bothered to ask who he was bringing—I didn’t give a shit. So you can imagine my shock when into the van climbs a familiar high-school dude…from our math class! A dude who made a habit of staring at Nikki and me so much that one day I even blew him a sarcastic kiss. OMG. WTF. That’s what Nikki and I would have been texting each other, but it was still the dark ages, so we had to sit there in silence. But here’s what we were both thinking: What a creep. What a weirdo. What the hell is he doing heeeere? He don’t belong here.

Sleeping in the van was awkward, but the dude behaved and didn’t perv on us. We got to see Radiohead perform “Creep,” as well as “My Iron Lung,” which would appear on next year’s masterpiece The Bends. And, really, that made it all worth it.

LISTEN: