Happy 30th Anniversary to Rage Against The Machine’s eponymous debut album Rage Against The Machine, originally released November 3, 1992.

“My first ad, that I put in the newspaper said: ‘Looking for neo-Marxist heavy metal singer who also likes Run-DMC,’” Tom Morello recalled during a 2018 SiriusXM interview.

Before Los Angeles-based Rage Against The Machine released their self-titled debut in 1992, no one had created an entire album of hip-hop/rock fusion. There were one-offs—Aerosmith and Run-DMC’s “Walk This Way (1986),” the Beastie Boys’ “Fight For Your Right (To Party)” (1986, five months later), Faith No More’s “Epic” (1990), and Public Enemy and Anthrax’s “Bring The Noise” (1991)—but never an entire album.

In fact, writer Geoff Edgers, who penned the 2019 book Walk This Way: Run-DMC, Aerosmith, and the Song That Changed American Music Forever, believes that “Walk This Way” had a profound influence on legitimizing hip-hop, and that when Aerosmith and Run-DMC literally broke down a wall separating their two groups in the 1986 video for “Walk This Way,” it was symbolic in a way not unlike the tearing down of the Berlin Wall only a few years later.

The video “sent a powerful message about rock and hip-hop being equally valid genres that didn’t have to exist separately,” Mental Floss observes. (Aerosmith had more to gain from the union—at that point, they were regarded mostly as ’70s has-beens who were experiencing a revival by proximity to a “new” genre.) “Walk This Way” was one of the first rap songs to play on mainstream radio, and it happened at a time when hip-hop was discriminatorily considered underground, “other,” and outside the mainstream (white) establishment. In a similar vein, by creating a whole new rap-rock genre rather than just a one-off radio hit, Rage Against The Machine furthered that cultural and political message, made all the more potent by their radical, left-leaning, and anti-racist lyrics.

After graduating from Harvard with a BA in political science in 1986, the same year “Walk This Way” was taking over the airwaves, Tom Morello moved to Los Angeles to become a rock star. He’d spent his teenage years (and even his Harvard years) practicing guitar for eight hours a day, attempting to emulate the complex stylings of Randy Rhoads. And now Morello wanted to be a guitar hero in his own right. His early months in LA were miserable: he couldn’t find a job because he was over-employable, he quickly burned through his $1000 in savings, and he ended up in a slew of low-income jobs in order to pay LA’s exorbitant rent, including working as a stripper (“Brick House” by the Commodores was his signature jam).

Eventually, he ended up finding a job in line with his education, in the office of senator Alan Cranston, a liberal Democrat lauded for his progressive stance on nuclear disarmament. Morello’s experience in Cranston’s office from 1987 to 1988 would leave him disillusioned with the political process, which would no doubt supply fodder for the incendiary, far-left, fuck-the-system politics of his eventual band Rage Against The Machine.

“If there was any ember burning in me, it was extinguished working in that job because of two things: One of them was the fact that 80 percent of the time I spent with the senator, he was on the phone asking rich people for money,” Morello recalled. “It just made me understand that the whole business was dirty. He had to compromise his entire being every day.”

After quitting the job, Morello joined a metal band called Lock Up, which eventually signed with Geffen and put out one album with the unfortunate title of Something Bitchin’ This Way Comes. Meanwhile, Zack de la Rocha, a young twentysomething six years Morello’s junior, was screaming revolutionary, hard-left lyrics in hardcore bands in the same city.

Watch the Official Videos (Playlist):

Morello and de La Rocha had a number of things in common. Morello was the son of Stephen Ngethe Njeroge, who later became the first ambassador of Kenya to the United Nations, and his uncle Jomo Kenyatta was the country’s first elected president, voted into office in 1964. Morello’s white American mother, Mary Morello, had met Njeroge while she was teaching English in Kenya and the Mau Mau rebellion erupted. Mary decided to abandon her fellow schoolteachers, and she met Njeroge at a pro-democracy rally in Nairobi, where they fell in love. The couple moved to Harlem, New York, where their son Tom was born, but they soon divorced, with Njeroge moving back to Kenya, and Mary moving back to her home state of Illinois to an all-white town called Libertyville, where, Morello told writer Rob Tannenbaum, he was “constantly aware of his Blackness.”

Zack de la Rocha’s parents, too, separated when he was young, and he shuttled between two households. His Mexican-American father, Roberto (“Beto”), had been a member of the Chicano art collective Los Four, and his large-scale, revolutionary paintings were included in the first Chicano art exhibit ever shown at the LA County Museum of Art, a huge source of pride for young Zack. Beto lived in poor East LA, while Zack’s mother Olivia, pursuing a PhD in anthropology at UC Irvine, lived in wealthy Orange County.

The stark disparity between the two environments had a profound effect on young Zack, in part because his father, who had suffered a nervous breakdown, would pour over the Bible in a darkened house, and some of his behaviors were unintentionally abusive (Beto would fast for long periods without food, and encourage Zack, who was still developing and needed nourishment, to do the same). Beto also destroyed several of his paintings and forced Zack to help him burn them. “I worry about what that experience did to me, how it affected my thinking,” Zack told SPIN writer R.J. Smith in 1996. “I think it affected me in good ways too, because I feel at this point, what could anyone do that could hurt me more?”

On the other hand, even though Zack’s home life with his mom Olivia was stable, Irvine was “one of the most racist cities imaginable.” He remembers an incident in high-school geology class, where the teacher referred to a border checkpoint in California as “the wetback station.” “I remember being very silent and feeling as if I could do nothing to raise my voice,” De La Rocha recalls. “At that point, I decided that when I started a band, I would never be silent again.”

Both young men gravitated toward music as a way to vent their frustrations. When Morello and de La Rocha finally found one another in 1991, Morello’s band Lock Up had just broken up and de La Rocha’s grungier, grassroots hardcore band Inside Out had also splintered (Zack wanted to add hip-hop to the mix, while another member wanted to infuse the music with a Hare Krishna vibe). And although Morello had just placed his ad for a neo-Marxist singer in the newspaper, it actually ended up being a mutual friend who introduced Morello and his pal, drummer Brad Wilk, to de La Rocha and his buddy since elementary school, bassist Tim Commerford.

They met in a mildewy room in some guy’s mom’s house and jammed. The chemistry was instantaneous. “From the first time the four of us got together in the room, something clicked,” Wilk recalls. “I don’t take chemistry for granted. We knew that we were onto something that was special to us and that we thought was unique.” The atmosphere was electric and, Wilk remembers, “Zack was like a lightning bolt.”

They decided to call themselves Rage Against The Machine, originally the name of a song de La Rocha wrote for one of his old hardcore bands. “We had no expectation of being able to play a show,” Morello admits. “We were perfectly content to make a cassette and sell it for $5 to anyone who would buy it.” They figured that a multi-ethnic band with revolutionary politics who were combining hardcore elements of fringe genres—hip-hop, hard rock, and hardcore punk—probably wouldn’t find an audience, even though the music came from their hearts. And yet they started playing shows—first at a house party, and then a gig at Cal State—and began amassing a rabid fanbase.

Within weeks of forming, the band recorded a 12-song demo tape, which they sold at shows. It quickly sold a surprising 5,000 copies, and Rage began sending the tape to various record companies. They secured a deal with Epic Records in early 1992 and were able to negotiate an arrangement where they were allowed absolute creative control, and no obligation for a specific number of albums. The result was Rage Against The Machine, a scathing critique of nearly everything American (and Western) society represented—wealth vs. poverty, war crimes of the government elite, the failures of education, the mental and physical enslavement of the masses (mostly via Capitalism) and, finally, police brutality (the album was recorded as the LA riots erupted in response to the Rodney King verdict).

As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism earns commissions from qualifying purchases.

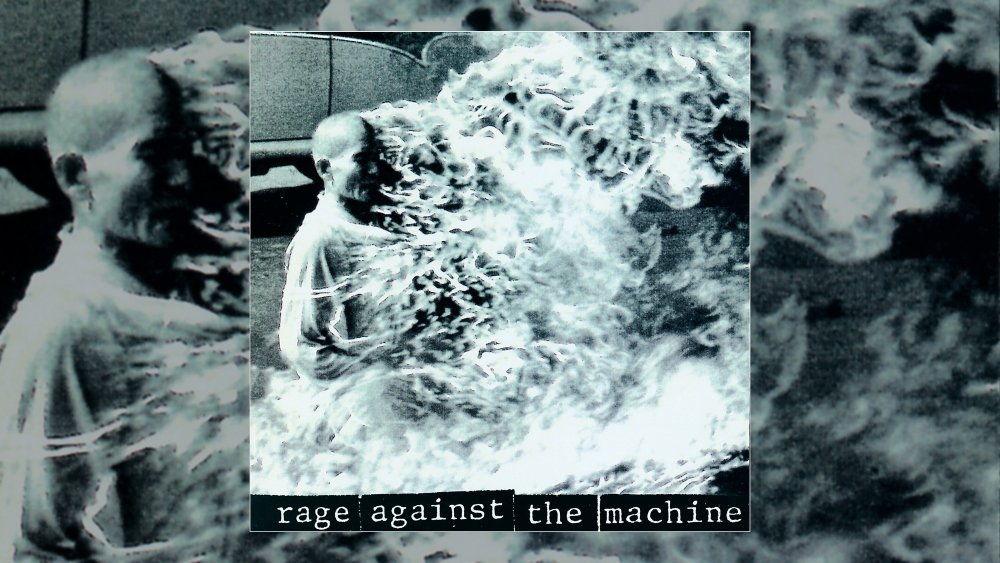

Rage Against The Machine, featuring a photo of the self-immolation of Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức, came out during my freshman year of high school and, although it was an immediate classic with metalheads, it took the alternative kids, including me, a little longer to appreciate. The drinking age in Germany was 16, and soon I was going out dancing every weekend at a nightclub called The Schwimmbad, where the DJ would play “Killing In The Name” and the dancefloor would explode into moshing with everyone yelling Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me. During my sophomore year in ’94, I’d attend the Rock Am Ring music festival, and mosh directly below a 24-year-old Zack de La Rocha shaking his dreads and screaming the exact same line. I imagine what I experienced was some of that same electricity—the same lightning-bolt energy—the four band members felt upon their initial meeting.

Rage likely opened with the album’s opener “Bombtrack,” because the performance is gloriously preserved on YouTube. The song begins with a funky bass riff, and then explodes as de La Rocha grunts “uhhhh” and adopts, right off the bat, the confident swagger of the best rappers as he boasts, “It’s just another bombtrack,” alerting us to a standard of high-quality throughout. The track alternates between a mellow groove and building walls of sludgy sound, until de La Rocha unleashes a scream, and suddenly it’s a lit fuse. It’s the perfect precursor to the anti-authoritarian “Killing In The Name,” the song everyone thinks of when they think of Rage Against The Machine.

“Killing In The Name” is a song of pure exhilaration, the kind that instantly makes one grateful to be young and alive. To create Rage’s wholly unique sound, Morello relied heavily on effects pedals, to the point that the band included in their liner notes: “No samples, keyboards or synthesizers used in the making of this record.” He’d scratch at his guitar strings, create metallic and laser-sounding effects, and coax out sounds that rarely emerged from a guitar. “I was basically the DJ in Rage,” Morello said in his entry as one of Rolling Stone’s 100 Greatest Guitarists.

Part of what makes “Killing In The Name” so infectious and unique is its odd drop-D tuning, an unusual tuning that became popular soon after. “I came up with that riff when I was teaching guitar lessons and I was showing someone how to do drop-D tuning,” he recalls in Know Your Enemy: The Story of Rage Against The Machine. “That riff just happened to spill out of my fingers. I had to stop the lesson and go record it. I feel very lucky that I did.”

Another key component to the success of “Killing In The Name” is the sparseness of the lyrics, which rely on the repetition of a few lines for the song’s fist-pumping power, rather than a wordy thesis. And then of course there’s the incendiary “Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me,” which makes for a seriously singalong chorus.

“Take The Power Back” starts with coiled, caterpillar-like sounds, and then de La Rocha establishes his full command, demanding that the band “crank the music up” and “bring that shit in.” His raps weave in and out of scratchy guitar riffs and rubbery bass lines with a deft flexibility, and then we’re back in that classroom with a young Zack, feeling his pain and anger, and yet this time he’s found his voice—“The present curriculum / I put my fist in ’em / Eurocentric every last one of ’em / See right through the red, white, and blue disguise / With lecture I puncture the structure of lies.”

“Settle For Nothing” is a track with a dark, slow, melancholy moodiness interspersed with interludes of screamo. It’s one of the pure hardcore songs on the album, with de La Rocha screaming his throat ragged with shrieks of “suiiiiiiicide” and “genooooociiiide.” It pairs perfectly with the next song, “Bullet In The Head.” In contrast to “Settle,” “Bullet In The Head” is wildly funk-infused, punctuated by sounds replicating sirens, and then it turns into a hardcore banger that breaks down and builds back up again while de La Rocha screams about the bullet in your head that’s keeping you from thinking for yourself.

The anti-war, anti-authoritarian “Know Your Enemy” features sick metal riffs and some vocals from Maynard James Keenan, of Tool, in the bridge section. It’s here we hear “Fight the war, fuck the norm,” and if you don’t flail around headbanging to this song, then what the hell is wrong with you? “Wake Up” is a chugging, grinding, suspenseful track that features a spoken-word section to critique the FBI for its targeting of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. “Fistful of Steel” features guitars that mimic high-pitched women’s screams, while “Township Rebellion” is a tribal, head-bopping, pounding call for healthy rebellion “in Johannesburg or South Central.”

Rage Against The Machine ends on “Freedom,” with De La Rocha reminding us that “The militant poet is in once again, check it” as his lyrics weave through chill-outs and dissolving breakdowns. The corresponding music video brought the plight of Leonard Peltier to the attention of MTV viewers, and the song completely dissolves at the end, with De La Rocha screaming “Freeeedom / Yeah, right.”

Though Rage didn’t usher in the radical revolution that they hoped to in the ‘90s (through no fault of their own), their music planted seeds in everyone who heard them then, and in everyone who continues to hear them with a rebel spirit in the decades beyond. Rage Against The Machine lived in people who participated in Occupy in 2011, in everyone who showed up to the Women’s March to protest Trump’s brand of Cheeto fascism in 2017, and it will be there in everyone who votes for women’s bodily autonomy this November.

“Rage made politics seem a very natural extension of the adolescent desire to forge your own identity, ask questions, and not buckle to what everyone else wants,” observes Dorian Lynskey, who’s studied generations of protest music, including Gen X. “It’s protest as instinct, as an emotional eruption.”

LISTEN: