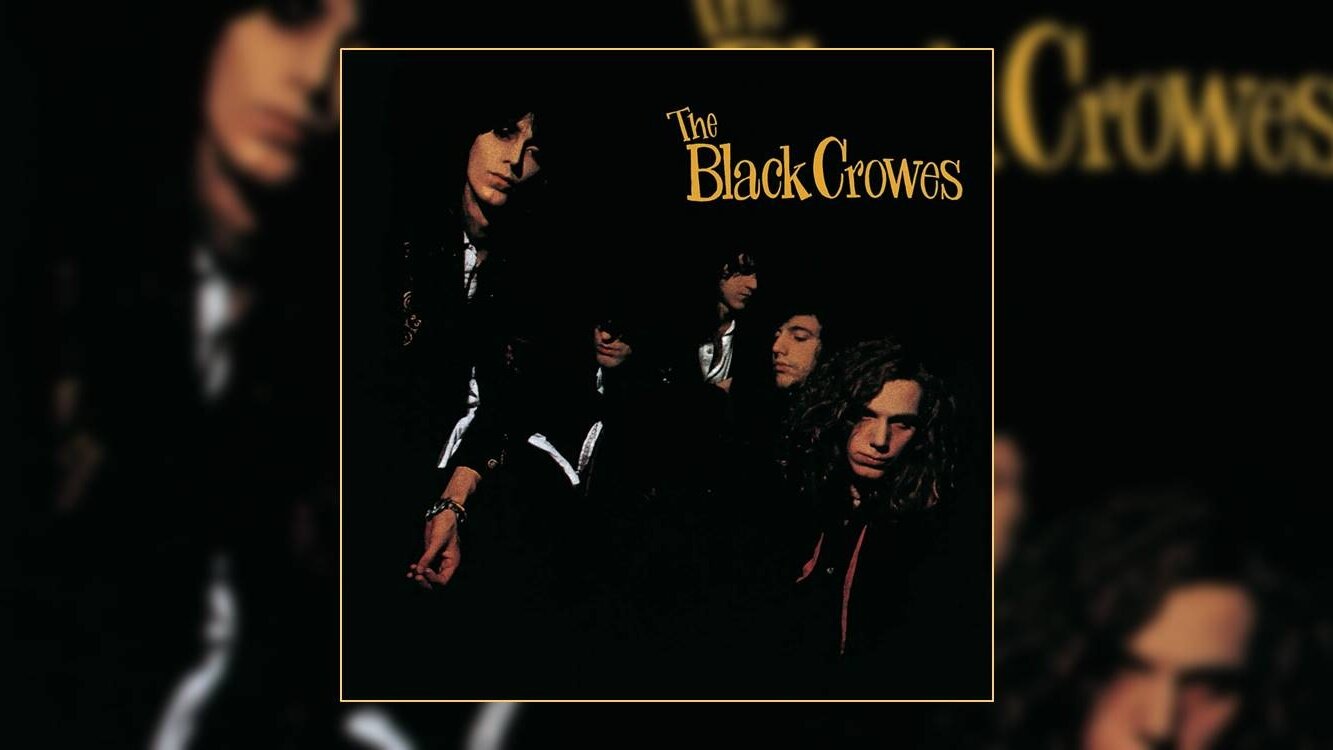

Happy 30th Anniversary to The Black Crowes’ debut album Shake Your Money Maker, originally released February 13, 1990.

Chances are if you grew up in the 1970s with an older sibling (or an uncle ten years your senior, as in my case) with a small but quality-based record collection, that by 1990, you may not have even needed to hear Shake Your Money Maker. Having already been schooled in the meat-and-potatoes rock of Faces' A Nod Is As Good As A Wink...To A Blind Horse (1971), Humble Pie's Smokin' (1972) or Performance: Rockin' The Fillmore (1971), Free's Fire and Water (1970) or the Rolling Stones' quad-attack from Beggars Banquet (1968) through Exile On Main St. (1972), you may have felt that you'd heard it all before. (All of these albums, incidentally, were released in that magical five-year span of 1968 through 1972.)

If you hadn't heard those records however, the debut album by The Black Crowes would probably have sounded like it came out of nowhere.

Wait. If you're reading this, I would assume that you're obviously a fan of Shake Your Money Maker, and that's great. But if you haven't heard all—or, shudder the thought, any—of the albums mentioned above yet, stop reading this right now and go find them. It's 2020 and they're all available for you to hear—I just checked. Those albums are all required listening to have any sort of context about the Black Crowes’ first album and its place in the rock & roll pantheon, or any of their subsequent albums actually, or rock & roll in general for that matter. Hell, even if you have heard them all, put them on again anyway, just because.

Okay, where was I?

By 1987, to quote Frank Zappa, "rock [had] gotten entirely too preposterous." The hair was big and the music was shallow. We didn't call it "hair metal" back then, by the way. That's a label that was affixed after the fact. It was just "pop-metal," "bubblegum metal," or, in some circles, "glam metal." Either way, it just wasn't the soul-blues-drenched-rock I was raised on. I had friends who were into it big time, though, so I tolerated what I could.

What stood out, however, was Guns n' Roses, who'd put out Appetite For Destruction that summer. It was unlike anything else at the time; it was more Aerosmith than that year's Permanent Vacation...by Aerosmith. You could practically smell the danger and attitude coming off AFD's cover and inner-sleeve.

The times were changing. Immediately following the success of Appetite, groups that had spent the last few years glammed-up and decked out in makeup and pastels, suddenly looked gritty, grimy, and encased in denim and leather. Groups that fit that sleaze-rock template were being sought after and signed. In Atlanta, some other guys around my age were noticing the turning tide as well.

Atlanta had spawned one of my all-time favorite bands, The Georgia Satellites, and they'd just recently hit it big with their self-titled debut, fueled by the number two classic, "Keep Your Hands to Yourself" (blocked from the top spot, tellingly at the time, by Bon Jovi's pandering and overblown "Livin' On A Prayer"). They were a bright spot in an otherwise dim landscape for a teenager searching for that elusive Stonesy-Faces swagger. Sadly, the Sats would only last for three albums and self-destruct by the end of the decade, but it's as if a ratty new bunch led by a pair of temperamental brothers heard the call and picked up the torch.

Originally christened Mr. Crowe's Garden, the band had made a name for itself touring up and back down the east coast and through the southeast in the late '80s. Drummer and Kentuckian Steve Gorman joined Chris Robinson and his brother, guitarist Rich Robinson, after splitting from Mary My Hope (which also included future Crowes bassist Sven Pipien) to join a band he felt had more drive. (Ironically, Mary My Hope broke first regionally, but ultimately fizzled nationally, possibly sounding more like '90s-era alternative rock than the world was ready for in 1989.)

Drive they had in spades. Direction and discipline? Not so much. Enter A&R mastermind George Drakoulias, a former college buddy of Rick Rubin, who was about to help the now legendary producer launch his new rock imprint, Def American Records, and he wanted Mr. Crowe’s Garden on board. But first, he needed to whip them into shape.

Like many college-aged kids in the south at the time, the Robinsons and Gorman were big fans of the left of the dial: R.E.M., The Replacements and their ilk with a dash of punk and folk. According to Gorman's memoir Hard to Handle: The Life and Death of The Black Crowes (written with Steven Hyden), Drakoulias heard potential and he guided them to embrace their inner rock stars. He took them to the woodshed armed with Stones records to listen to with fresh ears, introduced Rich to the mighty open G tuning, ultimately convinced them to change their name to The Black Crowes, and the rest is rock & roll history.

What sets Shake Your Money Maker apart from everything else on rock radio around its release in early 1990 is, quite frankly, its swagger. The open G tuning and rock-steady rhythm from Rich, the just-behind-the-beat groove from Gorman, the slinky low-end thump of Johnny Colt, and the Ron Wood-like crunchy attack of Jeff Cease. Soaring over it all was the once-in-a-generation wail of Chris Robinson.

Equal parts Rod Stewart and Steve Marriott in the pipes with moves like Jagger with a bit of Axl Rose's unpredictability, the older Robinson embodied everything a rock & roll frontman should be—including the massive ego. Another thing that set the Crowes apart from others in the pack was Chris Robinson's lyrics. They went beyond the surface of the cliched emotions of the typical rock music of the time and dug deep to where you felt the pain in his words.

You know the songs: the ominous slow slide riff that glides us into an avalanche of pure rock and roll on "Twice As Hard." The "Tumbling Dice" groove-and-weave of the mighty "Jealous Again." The Humble Pie-meets-Faces at their melancholy best on "Sister Luck." The sly attack of "Could I've Been So Blind." The slow, southern soul grind straight from Memphis and Muscle Shoals of "Seeing Things." The Otis Redding cover with the Aerosmith attack on "Hard To Handle." The whiplash tempo of "Thick'N'Thin." The Nick Drake-inspired jaw-dropping beauty of the now-classic "She Talks To Angels." The appropriately-named "Struttin' Blues" and the frenetic, anthemic, perfect-way-to-close-a-rock-and-roll-album "Stare It Cold."

The engineer on those songs? Brendan "Bud" O'Brien, who had played bass for a spell in the Georgia Satellites and would later become a highly sought after producer due to his work on Money Maker, working with everyone from Pearl Jam and ex-Satellite Dan Baird to Neil Young and Bruce Springsteen.

The Black Crowes gave us one hell of a set of songs right out of the gate. The band would eventually grow musically by leaps and bounds throughout their career, moving from "The Rolling Clones" to a genuine melting pot of roots rock and true Americana, influenced by the Stones, Faces, Free, and Humble Pie, yes, but also The Band, Allman Brothers, Little Feat, and many others.

Shake Your Money Maker isn't even their best album, nor was this the Crowes' best lineup. Both were to come next with The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion (1992) with the addition of Marc Ford (who replaced Jeff Cease) and keyboardist Eddie Harsch (the keys on Money Maker were handled by another Georgia boy, the legendary Chuck Leavell).

In fact, I don't think Money Maker is even in their top five when it's all said and done. What it is, though, is the sound of a young, hungry, and passionate band that waved the flag of real rock & roll by making an album that kicked rock radio and MTV in their collective asses and exposed them to true authenticity...at least for a little while.

LISTEN: