Happy 35th Anniversary to the Beastie Boys’ debut album Licensed To Ill, originally released November 15, 1986.

The impact of the Beastie Boys is hard to overstate. They are musical royalty. Comprised of Adam “King Ad-Rock” Horowitz, Mike “Mike D” Diamond, and the late Adam “MCA” Yauch, they are one of the most iconic groups to ever record music. They earned vast commercial and critical success. Seven of their albums went platinum or better. They also boast one of the most distinctive and creative sounds of any group in the last 50 years.

The contrast of Ad-Rock and Mike D’s nasally tones contrasted well with the gruffness of MCA’s voice. Musically, they were always interesting, setting trends for how they approached and recorded rap music. In 2012, they became the second rap group ever to be enshrined into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. And they are one of the few groups that managed to hold themselves together for close to three decades without ever breaking up or having one of the core members leave the group.

And, not to put too fine of a point on it, they are credited with introducing hip-hop music to a white audience, making it acceptable for young white kids and teens to listen to this form of music that was created within the Black and Latino communities of New York City in the late ’70s. And their influence began with their first album Licensed To Ill, released thirty years ago in November 1986.

The Beastie Boys’ background was certainly different than that of the rap pioneers that came before them. Ad-Rock, Mike D, and MCA were all Manhattan natives and students of the NYC punk scene, and the trio had their genesis as a punk band. Growing up, all three famously attended both punk and hip-hop shows that cropped up throughout Downtown Manhattan. They specialized almost exclusively in punk rock, until 1983, when they recorded “Cookie Puss,” their first hip-hop track.

In 1984, the Beastie Boys made the transition from punk band to rap threesome, and signed to Def Jam Records at the behest of their DJ, Rick Rubin, the NYU student who, along with Russell Simmons, co-founded the label. The trio started making moves right off the bat, securing a spot as the opening act on Madonna’s Like a Virgin tour. Soon thereafter, they hit the road with Run-DMC, Whodini, LL Cool J, and Timex Social Club on the Raising Hell tour, all before releasing their first Def Jam album.

Licensed To Ill remains an extremely enjoyable album, but it’s also an odd duck. Though it has enjoyed monumental success over the years (it eventually earned Diamond status from the RIAA for sales exceeding 10 million) and was immediately hailed as genius by magazines like Rolling Stone, at the time some viewed it as insincere. Yauch, Diamond, and Horowitz were ostensibly outsiders to the hip-hop scene, and some argued that Licensed To Ill was lampooning hip-hop music. For their part, the trio never denied their lineage, and argued that their respect for rap was deep and abiding. That outsiders like the Beastie Boys were able to create such an enduring album is part of what makes Licensed To Ill a classic.

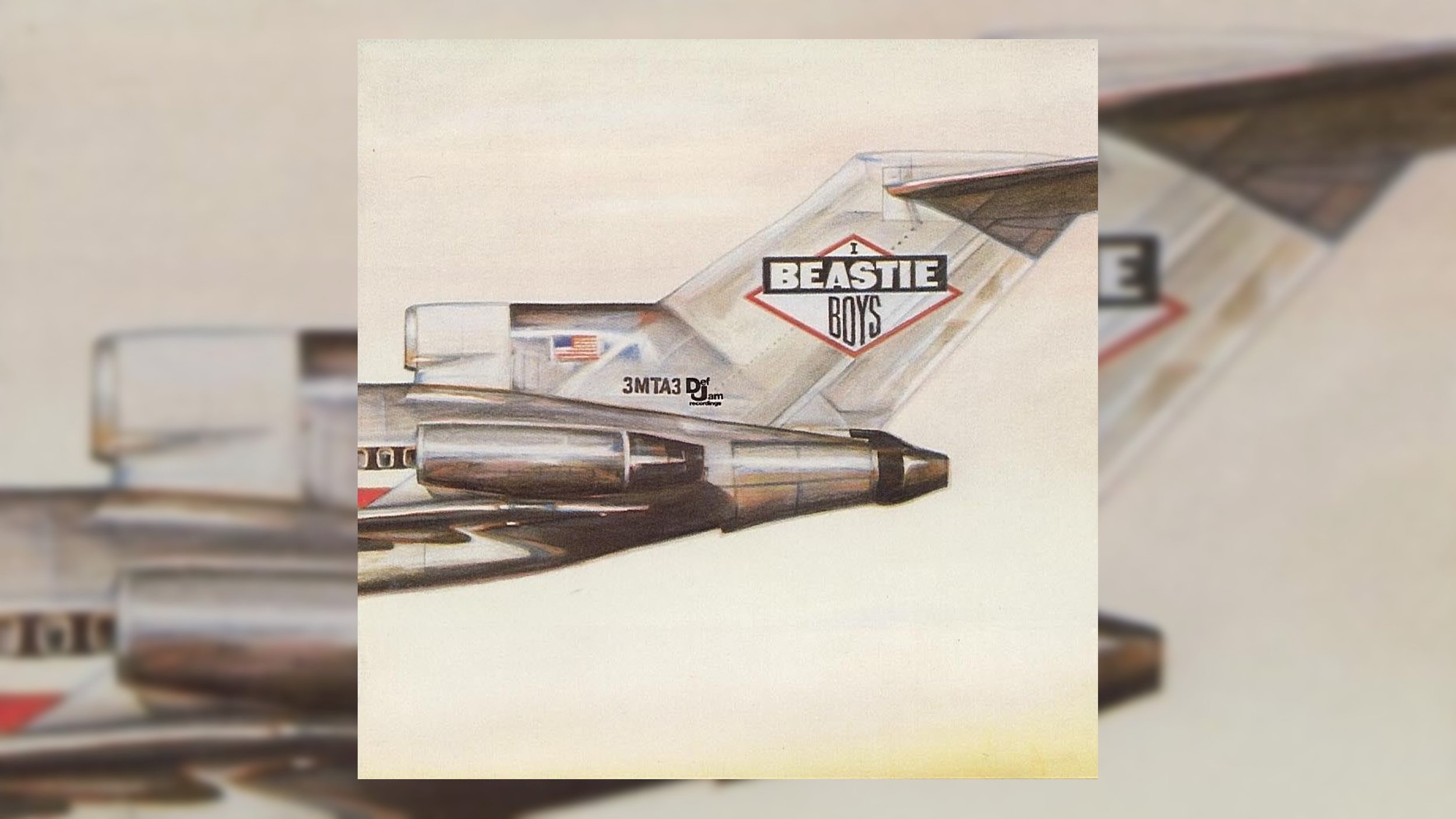

Over the decades, a lot has been made about Licensed To Ill’s relatively juvenile content and execution. The group originally wanted the album to be named, regrettably, Don’t Be A Faggot. The album cover has “Eat Me” written backwards on it. Their lyrics seem to embrace their image of “beer drinking, breath stinking, sniffing glue” degenerates. They cultivated a public persona of being more apt to inhale copious amounts of whippits than to hone their craft to become better emcees.

And as a result, there has been a considerable amount of debate surrounding how much of their public personas was meant to be taken seriously. It was an image crafted by Long Island native Rick Rubin, a product of the ’70s rock scene that the Manhattan-bred Beasties initially thought was funny and decided to play to the hilt. They wore it like a 2000-era Park Slope hipster sported a trucker hat, and didn’t let up until they nearly dissolved from burnout and bitterness.

A big part of the group’s appeal was the musical backdrop that they rapped over. To say the beats were “sampled” is inaccurate, since the album was recorded before the first samplers were widely commercially available. Rubin holds that the music was provided either by the DJ spinning the original records “live,” or through looping of the beats on tape in the studio. No matter what the means, the musical sources for much of Licensed To Ill came from records by hard rock and heavy metal groups like Led Zeppelin, AC/DC, and Black Sabbath. And there were copious amounts of live electric guitar, even more so than the early Run-DMC records. It resulted in a sound palette that was different than the vast majority of hip-hop records released up to that point, as many of their hip-hop contemporaries did not gravitate towards rapping over these so-called “white” records.

However, the argument that the Beastie Boys were the first white rap group that “rapped like they were white” has always been misguided. Licensed To Ill is an album that is supremely reverential to their rap influences, like the aforementioned Run-DMC, Spoonie Gee, K-Rob & Rammellzee, or the Cold Crush Brothers. Indeed, the album comes from a place of love and reverence for hip-hop’s forefathers. It remains pretty much an old school hip-hop album in which they rap over rock records instead of ’70s disco. And truthfully, they rhyme to their fair share of ’70s disco as well.

Licensed To Ill certainly starts off on the hard rock note with “Rhymin & Stealin.” Backed by thunderous drums of Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks” and the blistering guitars lifted from Black Sabbath’s “Sweet Leaf,” the three start the album shouting their lyrics with reckless abandon. They throw themselves into their roles as b-boy pirates by “snatching gold chains and vicking pieces of eight” and “skirt chasing, free-basing, killing every village” while drinking, robbing, and pillaging. However, given the pirate/high seas theme that runs through the track, the “ALI BABA AND FORTY THIEVES!” refrain that appears midway through the song never made much sense.

On “The New Style,” the Beasties take a straightforward “beats and lyrics” approach to the music, all three emcees trading short verses and ill routines back and forth over solid breaks and electric guitars stabs. Mike D’s lines, “If I played guitar I’d be Jimmy Page / The girlies I like are underage” remains one of the group’s most clever lyrics, even if it’s a bit ill-advised in hindsight. When the tempo flips towards the end of the track, after Ad-Rock’s infamous “Kick it over here, Baby Pop!” interlude, it makes the track feel even more epic. However, Mike D did later admit that the track presented “a fantasy version of our actual lives.”

Songs like “Posse in Effect” and “Time to Get Ill” further demonstrate that the Beastie Boys were excellent at structuring a straightforward, no gimmicks hip-hop song. Both tracks are rugged crowd-pleasers, while the Latin-influenced “Slow Ride” is the most car-friendly entry on Licensed To Ill.

One of the reasons that the Beastie Boys wore their Run-DMC influences on their sleeves is because the venerated crew wrote and conceptualized a pair of tracks on Licensed To Ill. One is “Slow and Low,” which was originally recorded by the Hollis, Queens legends during their King of Rock sessions. The Beasties loved the song and were baffled that Run-DMC left it off the album.

The demo version of Run-DMC’s track features the same rhymes, thumping drums, and cowbell/percussion patterns. Rubin added blaring guitars courtesy of AC/DC’s “Flick of the Switch,” and added some distortion to the Beasties’ vocals on the chorus. The revised product unsurprisingly sounds like a Beastie Boys version of a Run-DMC song, albeit an iconic one.

Run-DMC also came up with one of the most beloved tracks on Licensed To Ill, “Paul Revere.” It’s a ridiculous tale of the Beasties as outlaws riding horseback on the high plains, low on beer and on the run from a posse due to committing unnatural acts with the sheriff’s daughter, with a wiffle ball bat no less. All three eventually unite at a dusty saloon, decide to rob the place, and make off with gold, women, and cold beer.

For all of its goofiness, “Paul Revere” still maintains its magnetic charm after three-and-a-half decades. It’s the type of song that made me, as a sixth grader, immediately know that I was going to commit myself to learning and memorizing the lyrics. It’s a song that probably inspired hundreds, if not thousands, of bad junior high school plays. And listening to it 30 years later, it’s the type of song that still puts a smile on your face.

“Hold It Now, Hit It” was the third single from the album and, according to Mike D in The Beastie Boys book, the song that “changed everything.” It was huge in legendary NY clubs like Latin Quarter and got major airplay on the venerated NYC mix shows on the radio. Its success helped put Def Jam on the map as a label. It’s the most straight-ahead rap track on the album, with all three members continuously dropping one to two bars, then passing the mic. The continuous flow of lines over the bouncy conga beat gives the track an infectious groove, punctuated by the breakdown featuring drums from Trouble Funk, scratches from Kurtis Blow, and Slick Rick vocals.

In the Beastie Boys book, Mike D wrote about how the song, produced by Ad-Rock, was formative in helping the group come into its own. “Instead of trying to act and sound like someone else,” he explains. “we were just being ourselves, writing from our own lives and experiences … We figured out how to piece together different elements from what we loved … and turn them into a song.”

“Hold It Now…” was also the source of one of the first sample clearance lawsuits, as Jimmy Castor sued the Beasties and Def Jam for using large elements of his “Return of Leroy” record without his permission. The group settled out of court, and agreed to give Castor some percentage of the profits from Licensed to Ill.

When most people speak of Licensed To Ill’s more juvenile nature, they’re usually referring to “Girls” and “Fight For Your Right To Party,” the final two tracks on side A (tracks 6 and 7 for those of you out there who only know this album from the streaming version). They are probably the two worst tracks on the album, but both decently enjoyable.

“Girls” is the more light-hearted of the two, and probably the sparsest track on the album. The track, which is essentially an Ad-Rock solo track, features just a drum machine, xylophone, and background vocals by MCA and Mike D. The rhymes are pretty immature, but the whole two minute and thirty second song is so slight it can barely be taken seriously.

Meanwhile, the similarly infantile “Fight For Your Right To Party” launched the Beastie Boys into super-stardom. While “Hold It Now…” may have broken the Beasties to hip-hop audiences, “Fight For Your Right…” made them household names with the MTV generation. MCA and a friend of his wrote the song with the intention of recording it as part of a side project they were working on. The reality that a song that was “practically a throwaway” became a global hit baffled the trio.

The blaring guitar-driven song, a goof on the “party hard” lifestyle and songs of the late ’70s and early ’80s, was accompanied by an equally ridiculous video that received regular rotation on the music video channel. Looking back, the song was a pretty obvious joke, but nonetheless listeners took it seriously.

For better or for worse, the song defined the group early in its career. It fit within the white trash aesthetic that Rubin had designed for the Beastie Boys, and they milked it extensively on record and in concert. Gradually they grew to hate the song, especially after playing it incessantly during their first headlining nationwide tour, a tour that ended up almost destroying the group. Reportedly the group never performed “Fight For Your Right” live again after 1987. The revulsion to its success is one of the reasons the trio ended up leaving Def Jam, but we’ll get to that later.

“Brass Monkey” also appeals to the Beasties’ more juvenile side, as it is their ode to drinking a mix of malt liquor and orange juice out of a 40 oz. bottle. Just thinking about consuming this particular “cocktail” is vomit-inducing, but the song is goofy fun regardless. Over a break from Wild Sugar’s “Bring It Here,” the Beasties merrily sing the merits of drinking this vile concoction while walking the streets of Manhattan and hanging out by their high school lockers. Why anyone would prefer malt liquor and OJ to Moet or Chivas is beyond my understanding, but it probably has something to do with being young and dumb. Also, given the rampant profanity in hip-hop music from the late ’80s on, it’s an entertaining oddity to hear the group censor itself towards the end of the song.

“No Sleep Till Brooklyn,” the album’s sixth single, remains one of the best rap songs about touring, though it’s the album’s most straight-up metal song. Accompanied by Slayer’s guitarist Kerry King, the group reflects on the non-stop insanity of touring, learning to deal with “Another plane / another train / another bottle in the brain / another girl / another fight / another drive all night” as well as their dusted manager.

Touring became very much an unbearable slog for the Beasties, as did their own popularity. The success of Licensed To Ill album and the accompanying tour nearly did the group in. Both Ad-Rock and Mike D have said after the tour ended, the group members were sick of each other, sick of the band itself, and sick of the “self-parody that we had become.” Both Simmons and Rubin wanted the group to start recording another album immediately to capitalize on Licensed to Ill’s massive success. The three Beasties balked, and eventually left Def Jam, then recognized as hip-hop’s premier label, for Capitol Records, known as the home of The Beatles. The group stuck with Capitol for the remainder of their recording career.

The Beasties built a storied career while on Capitol. They released the groundbreaking sleeper Paul’s Boutique (1989), and afterwards incorporated the extensive use of live instrumentation into their music on albums like Check Your Head (1992) and Ill Communication (1994). The latter, of course, features their other universally embraced single, the nouveau punk-rock anthem “Sabotage.” However, it would be wildly inaccurate to imply that the Beastie Boys ever abandoned rap music. Large chunks of their post Licensed To Ill output are love letters to old school hip-hop, and later albums featured the group’s return to its straight-ahead hip-hop roots.

The Beasties may have a complicated relationship with Licensed To Ill, recognizing that they both like and hate it. They eventually made peace with the legacy of “Fight For Your Right To Party” on Hot Sauce Committee, Pt. 2 (2011), referencing it extensively on “Make Some Noise,” one of the album’s singles. Other songs from Licensed like “Slow And Low,” “New Style,” and “Time To Get Ill” remained staples of their live performances. However, it’s never been clear whether the Beastie Boys ever made peace with Simmons and Rubin.

In the Beastie Boys’ long and decorated career, Licensed To Ill is an interesting first step. Yes, it’s absurd and silly in all the ways that you’d expect a largely ironic frat-rap album from the mid-1980s would be, but it still possesses a lasting charm that’s impossible to shake. It’s kind of beside the point whether or not the album was ever meant to be taken seriously, because much of it is firmly rooted in solid, old school hip-hop sensibilities, and the music stands on its own. “Fight For Your Right To Party” may have become a standard of Bar Mitzvahs, weddings, and bad cover bands, but it’s “Paul Revere” that rides forever.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.