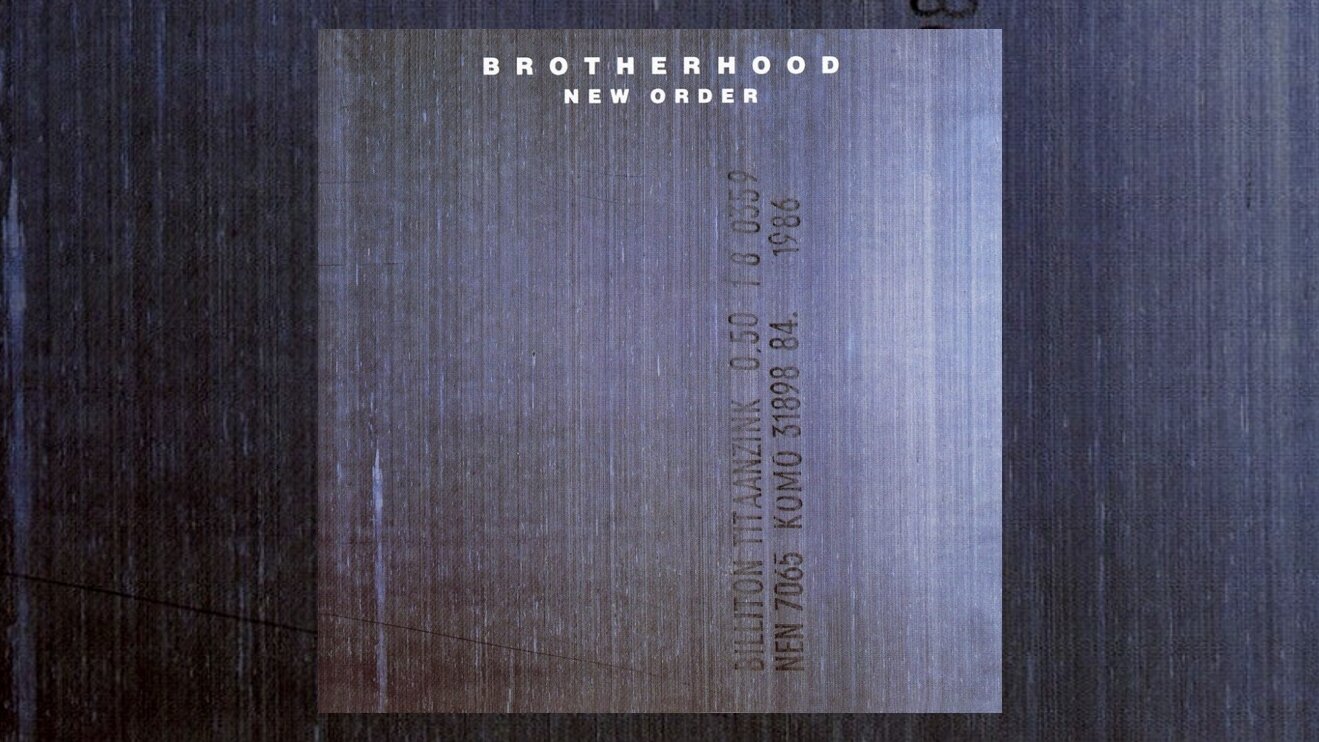

Happy 35th Anniversary to New Order’s fourth studio album Brotherhood, originally released September 29, 1986.

New Order built the bridge between two continents divided by snobbery and ignorance. By the early ‘80s, New Wave had firmly planted its seeds into punk’s unstable soil. However, the appearance of keyboards and drum machines angered purists like Iggy Pop and Henry Rollins. A decade or so later, Rollins, his trademark sardonic sneer in full swing, responded to Depeche Mode’s decision to use live drums during the band’s Songs of Faith and Devotion (1993) by exclaiming, “Wow, what a novel concept!”

In a similar snarky vein, you may recall Iggy Pop’s infamous limousine meltdown following his emergency exit from the 2007 Caprices Festival in Switzerland, an event that EDM artists had closed out, in which he screamed at reporters, leaning out from his rolled-down window, “It’s the fucking techno—before and after—fucking hate that fucking techno shit! I will fight you until I die—techno dogs and fucking push-button drum machines.” Had Pop forgotten his spoken word storyline on Death in Vegas’ 1999 single “Aisha?”

Before Digital Audio Workstations like Ableton made programming and quantizing drum patterns a point-and-click and drag-and-drop walk in the park, the earliest versions of Wurlitzers, Eko’s, and 808’s were not the easiest devices to operate. Devo’s use of the Linn LM1 on 1980’s New Traditionalists’ “Working in the Coal Mine” fit the song’s industrial theme, allowing for the song’s irony to match the great band’s deep red energy domes. Afrika Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock” fused hip-hop and Afrofuturism to Kraftwerk and Yellow Magic Orchestra. What Bambaataa built from the refined parts of others facilitated hip-hop’s embrace of European dance music. Yet, caked-on eyeliner and oversized keytars repulsed—and threatened—the hyper-masculine rockers and their traditional reverence for the guitar-bass-drums-charismatic lead singer motif.

Post-punk became a convenient category concocted to separate The Clash, the Ramones and the Sex Pistols from their latter-day acolytes. But Joy Division were a punk band at their core. Even their name referenced an obscure Nazi sex trafficking camp, keeping in line with punk’s anti-fascist attitude. An Ideal for Living’s opening track “Warsaw” competes with the same ferocity as “Holiday in the Sun” or “Blitzkrieg Bop.” Rawer and impure, it preceded Martin Hannett’s experimental production techniques found in the band’s only two full-length albums, Unknown Pleasures (1979) and Closer (1980), changing the shape of punk to come.

Closer incorporated keyboards, and if it were not for the band’s trust in Hannett’s peculiar, but trusted, suggestion to use a Boss DR55 drum machine and Synare drum synth, the post-punk sound would belong exclusively to Wire and Gang of Four. “Atrocity Exhibition,” Closer’s opener, used synth drones. “Isolation” built its signature riff with a synth held together by bassist Peter Hook’s driving low-end sound. “Decades” closed the album with the same foggy drifts and murky atmosphere found in its invocation. Dark, disparate and gloomy, no one would have anticipated the remaining three musicians would subsequently create one of the greatest dance singles of all time, “Bizarre Love Triangle.”

The bridge to nowhere connected the divide, creating a hybrid of rock and electronic music bonding the once polarizing forces by exposing their shared traits. New Order’s 1986 fourth studio album Brotherhood presents the band at their peak. Every song a single, each track becomes a pattern still imitated by the best, and worst, in indie rock. Hook once exclaimed about the album, “Listen to it, and you can hear it has two different sides. There were battles raging on Brotherhood.” De-facto lead singer, multi-instrumentalist and songwriter Bernard Sumner echoed Hook’s sentiments: “We’d always had that balance of electronics and band stuff. I was always pushing for electronics, and Hooky was always pushing for the band stuff, which was fair enough, I think. And by luck it tipped the band that way on Brotherhood. It was a very dense album, because we’d gone a bit mad on overdubs, so it was very layered, and very dense.”

The push-and-pull dynamic begins with the first songs on the album’s two sides. Side A’s opener “Paradise” drops a synth bassline accompanied by a melodic mid-range bass riff performed by Hook. Alone, both basslines are far from unique. Blended together, they converged like a head-on collision—the rare sort where both parties come out unscathed. The synth-driven, vocoder-heavy Goliath “Bizarre Love Triangle” made people dance to that fine, fine music about a person too ambivalent to make up his or her mind about who he or she wants. Where “Blue Monday” launched early house music into the mainstream, “Bizarre Love Triangle” made it acceptable to write pop songs with drum machines and guitars, while the band’s drummer, Stephen Morris, had placed the sticks down and descended from his kit to play keyboards.

Brotherhood is more than the glorious “Bizarre Love Triangle,” which is not the album’s best track, as it turns out. New Order left no stone unturned on “Broken Promise.” Peter Hook reveals flashes of Joy Division’s past with bass riffs driving through the broken hearted like a freight train. Gillian Gilbert plays keys buried deep in the mix. Morris’ performance also reflects his nascent days, performing in Manchester dives, his robotic rhythms trademarked by his use of toms and heavy kick drums. The only thing distinguishing it from the Hannett-produced predecessors is the ‘80s obsessed reverb washing over each snare hit. Ashes and charred edifices lie in the track’s remains, and its signature lyric graffiti’s the heart in the way “Bizarre Love Triangle” could not: “There’s a fire in life where we will burn.”

Crises are responsible for great albums. Bands crash and burn after swift stylistic pivots. Metallica, for instance, will recover from their disastrous collaboration with the late, great Lou Reed. And Load stood on the last nerve of fans who married themselves to the band, for better or worse. Brotherhood’s longest track, “All Day Long,” rests on repetition, but expands on delight. The layers of overdubs that Sumner discussed come into full view. “As It Was When It Was” buds with a Velvet Underground-styled intro, yet it flowers into an extraordinary jam that barely resembles the riff with which it begins.

When CDs arrived as the more permanent alternative to cassettes in the mid ‘80s, the band added the obvious single “State of the Nation.” With its chorus repeated to the point of engendering a migraine, the track was a poorly chosen second to the album’s monolithic dance hit. Bearing the album’s only flaw, the logic to follow up a dance single with another remixable dance single, made sense. It deliberately sold their greatest album short, preventing the hybrid pieces to ever see the light of day.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.