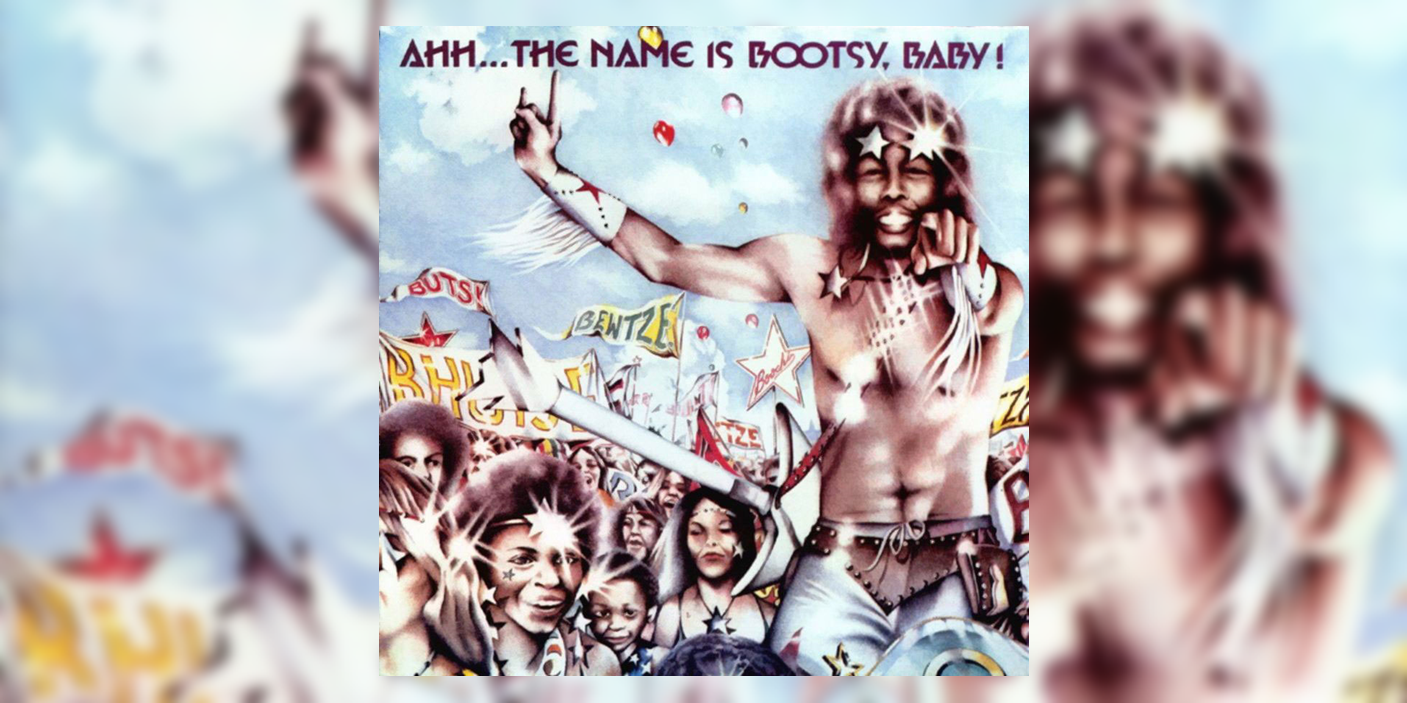

Happy 45th Anniversary to Bootsy’s Rubber Band’s Ahh...The Name Is Bootsy, Baby!, originally released January 15, 1977.

“Uh, say Bootsy—you’re a superstar, right?”

If ever a funk encyclopedia existed, William “Bootsy” Collins’ name would sit proudly under the distinction of being “funk’s brightest star.” In his illustrious six-decade career, the Cincinnati, Ohio-bred funk legend brought the entire planet to his Psychoticbumpschool, with a cosmic fusion of wicked cleverness, smoking-hot grooves, and whimsical humor only he could muster up.

When he joined the ranks of funk godfather James Brown’s masterclass, he carved out his own vision for what funk can do and aspire to be. It was during his crucial tenure with the 1969-71 incarnation of Brown’s backing band, the J.B.’s, that a teenaged Collins laid the funk gavel down on seminal touchstones like “Get Up (I Feel Like Being a) Sex Machine,” “Super Bad,” “Soul Power,” “Talkin’ Loud and Sayin’ Nothing,” “Ain’t It Funky Now,” “It’s a New Day,” and “Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved,” while rejuvenating Brown’s funk edge for the young, gifted, and Black era. He singlehandedly revolutionized the anatomy of the funk groove for generations to come.

His influential style as a bass virtuoso epitomized gut-bucket, deep-in-the-pocket ‘funkativity’ that couldn’t be taught in a music course or defined on some jive piece of sheet music. It was street, young, sexy, and downright euphoric. The syncopated precision and tight improvisation he utilized in his approach served as the very charm of ‘the One’—a groundbreaking methodology Collins learned from the James Brown playbook during his J.B.’s days, where a song’s rhythm is anchored around the first pulse of a four-beat measure. In one distance, he embodied James Jamerson’s ubiquitous bass style that spearheaded the simplicity and innocence of prime-era Motown, but he incorporated immense charisma in whatever he played.

More importantly, Collins’ shapeshifting funk employed much of the freewheeling spirit from two of his biggest heroes, Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone, with an unmatched urgency that could bridge all musical barriers. His knack for chiseling a groove was never about being pinned down by a certain tradition or convention. It was about the freedom of taking a groove far and beyond its restrictions.

After his 100-yard dash down James Brown’s jungle groove came to an end in 1971, Collins packed his groove arsenal and marched down the chocolate-coated, freaky, and in habit streets of Detroit, where he met funk mastermind George Clinton. It was a true meeting of the minds, as both of their musical visions and extravagant personalities blended compellingly. It was with their seamless partnership that George Clinton’s P-Funk empire (Parliament-Funkadelic) was destined to grow into the ultimate funk experience.

From 1972 onward, Collins bestowed his funk thumping dynamism upon the wildly eccentric and insanely lysergic Parliament-Funkadelic army. As the turbulent 1970s soldiered on, the funk got stronger and the Mothership encapsulated a sea change in the entire musical landscape, blurring the boundaries between science fiction and social realism with an idiosyncratic musical vision. From their elaborate stage show extravaganzas that became as legendary as their outlandish personas to their unparalleled run of ambitious album-length statements, P-Funk dropped their own funk philosophy, mythology and socio-spiritual ethos onto the globe with one fundamental goal: freeing the minds of the People to let them dance out of their constrictions.

In 1975, Collins secured a record deal with Warner Brothers and recruited an all-star posse of musicians and personalities that would become Collins’ backing band, Bootsy’s Rubber Band, as well as members of the P-Funk mob to give a helping hand. By that following year, the band released their audacious debut LP, Stretchin’ out in Bootsy’s Rubber Band, setting a new precedent for the funk generation with stone-to-the-bone grooving and psychedelic soul balladry that appealed to young P-Funk fans (commonly referred to as ‘geepies.’) George Clinton understood that Collins’ bubbly charisma and humor could broaden their funk approach and reach other demographics. It certainly worked. In establishing his identity, Collins adopted an outrageous look where he wore star-shaped mirror glasses and took on several personas like Casper, the Sugar Crook, Chocolate Star, The Player, and later, a Black wind-up rhinestone rock-star doll named, Bootzilla.

The Mothership Connection was in full levitation and had no signs of crashing, yet strong conflicts were brewing in the music landscape. Disco exploded in every facet of the mainstream, permeating in spaces that it had previously been restricted from before. The raw power of the funk groove was transitioning, leading several of its founders and soldiers to either regress from their current glories or move in stride. The P-Funk collective certainly saw the tides as they turned and stuck to their guns, or shall I say their “Bop Guns.” If 1976 saw the ascension of an intergalactic funk diaspora created by extraterrestrial afro-naunts striving to push the freedom of thought and being to the People, then 1977 would mark the flagship celebration of their staying power with “the Bomb,” a funk methodology that the P-Funk crew had been relishing in since the earlier bluesy, acid-rock and soul freakout of Funkadelic.

Who better to kick off “the Bomb” in ‘77 than their rhinestone-studded, leather-spangled superhero, who gave up the funk proudly with his monstrous ‘Space Bass’ clutched and ready to roll?

Bootsy’s Rubber Band silenced everyone with the spacey, streetwise funk of their debut album, Stretchin’ out in Bootsy’s Rubber Band and following up a classic of that magnitude was no easy task. Certainly with their next release, 1977’s Ahh… The Name is Bootsy, Baby! , Collins avoided the sophomore jinx and came up with the greatest achievement of his career. Recorded at the “P-Funk Labs” United Sound Studios in Detroit, Michigan and Hollywood Sound Studios in Hollywood, California, Collins and his partner George Clinton took their oversized personalities and wild absurdities to new plateaus, while expanding their elastic grooves to cohesively suit the dancefloor as well as the bedroom. Ahh… picks up exactly where Stretchin’ left off, but there is an unequivocal polish and experimental edge to the grooves that underscored just how ubiquitous the P-Funk sound had become by 1977.

There is no dud anywhere on this masterwork, as every musician and entity hits their peak, delivering rich spells of soul, rock, and jazz under the name of polyrhythmic funk, of course. There are none of the heavy Afro-futuristic theatrics anchoring the music. Every space of studio technology, complete with tape overdubs and reverb tricks, is occupied. No moment is wasted at the expense of the slapstick satire, goofball humor, and delectable nursery rhymes that are infused inside its intricate grooves. In fact, this remains some of the most idiosyncratic, multi-faceted, and in-your-face party music ever conceived. While this is certainly a George Clinton production with many of the hallmarks one would find in any of Parliament’s key 1975-1979 work, this is Collins’ show. It’s the inaugural party where fellow geepies, rubber fans, and funkateers championed their hero as the commanding officer of funk.

The first side, subtitled as “A Friendly Boo,” is Collins’ definitive emblem to high-level funkmanship and groovability. It was for the party people by the party people. It opens with the album’s title track, a jam that served as the opening for many of Collins’ live shows, particularly his first tour in 1976. Under the canned live ambience and swanky funk groove, the first voice that is heard comes from fellow J.B.’s and Horny Horns member Maceo Parker, who serves as the MC setting the scene and calling on the reemergence of Bootsy. Casper, one of Collins’ many personas, interacts with a mob of geepies who anticipate Bootsy’s return to free their minds with his game-changing groove.

When Bootsy finally appears, the groove gets deeper with him doing some funky riffing on his Space Bass and showcasing his coke-fueled cleverness, by gleefully crooning a refrain from the jazz standard “All of Me.” On one hand, there are elements that shouldn’t work in a multi-dimensional jam of this caliber, but collectively, they make it all the more irresistible and classic. The most undeniably genius moment comes at the very end, when Collins turns up the fuzzbox on his Space Bass and interpolates a rousing interpretation of “Auld Lang Syne” that recalls Band of Gypsys-era Hendrix and Eddie Hazel all in the same space.

The funk doesn’t let up with the album’s lead single “The Pinocchio Theory,” which Collins once declared to be “the ‘funkayest’ single of all-time.” With Collins’ pulsating bass thumps, the chicken-scratch guitar licks, and Joel “Razor Sharp” Johnson’s subtle clavinet work sprinkled on top of the infectious groove, the song serves as the centerpiece of Ahh… as a whole and remains Collins’ signature jam. The song’s memorable tagline, “you fake the funk, your nose got to grow” was the impetus for the Sir Nose D’Voidoffunk saga that was dramatized on Parliament’s 1977 masterpiece Funkentelchy vs. the Placebo Syndrome.

Two of the amazing dynamics of this classic funk sing-a-long were the hypnotic chord progressions and Collins’ progressive approach in utilizing groove movements. Just like the album’s title track, the hard-hitting groove of “Pinocchio” possesses an undeniable accessibility, while transforming into something else. During the brief bridge, Collins interpolates the bassline of Curtis Mayfield’s 1972 hit “Freddie’s Dead,” after breaking into the melody of the “Ring Around the Rosie” nursery rhyme, and then he goes back into his own groove. It just solidifies how much he developed his own sense of “the One.” “Rubber Duckie” is quite possibly, the album’s most overlooked moment, with its heavy disco leanings and slinky rhythms dominating the entire groove.

The second half, subtitled “Geepieland Music,” contains the most esoteric balladry Collins ever committed to tape, surpassing even Stretchin’ Out In A Rubber Band’s seminal ballad standout, “I’d Rather Be With You.” As the delicate melody of “What’s A Telephone Bill?” unfolds, you can’t help but to be swept up in Collins’ “verbal rappability” and “sweet naughty-nothings” while chuckling at the same time. “Telephone Bill” isn’t your average love song, as it is based on double-entendres related to telephones. Collins wrote it after a series of situations in which he picked up large telephone bills from making several phone calls to a female acquaintance he cared about. With Collins’ powerful bass improvisation and Gary “Mudbone” Cooper’s honeyed falsetto caressing the groove, the song proved to be a huge leap for Collins, cementing his place as the leading master of the funk ballad.

Things are taken up an even higher notch with the epic “Munchies for Your Love.” For nine minutes, you are transported to another world, as Collins takes hold of your metaphysical soul and intellectual senses, while letting his psychedelic funk wizardry soak up the entire atmosphere. This ballad is built-up with orgiastic tension, beginning with a slow vamp that is so soulful and serene that you get drawn into the groove immediately.

The groove gets heavier and eventually goes into a dramatic climax, with Collins’ fuzzy bass tones intertwining with Jerome Bailey’s frantic drumming. This remains the peak of Collins’ improvisatory approach as a musician. Ironically enough, this is not even a ballad devoted to sex, as its metaphorical lyrics would lead one to believe. It happened to be recorded one night when Collins and his band were tuning up their instruments and it turned into a jam devoted to his love of the bass. At any rate, it became the anthem that all funkateers, lovers, and rockers worshipped alike. The masterpiece concludes with the album’s second single, “Can’t Stay Away,” a sweet ditty with a groove that paid homage to Collins’ early days as a J.B.’s disciple. There is a strong Detroit soul influence that creeps in the song, as Collins, Mudbone, and Robert “P-Nut” Johnson trade vocal leads, in true Parliament tradition.

The commercial fruits of Collins’ gold-selling masterpiece were mightily sweet, as the album peaked on Billboard’s US Albums chart at number sixteen and the R&B/Soul Albums chart at number one in April of 1977. It became the first album in the P-Funk pantheon to achieve that goal and furthered Collins’ reputation as a stone-cold master of intrinsic humor and rump-shaking funk. He may have taken his extravagant personas up a notch with memorable figures like Bootzilla and co-piloted the P-Funk ship in their outrageous endeavors after this gem, but Ahh… The Name is Bootsy, Baby represents the true turning point of the funk superstar who took the funk groove beyond its limits forever. He marked his territory, and the Bomb still ticks forty-five years later.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2017 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.