Happy 30th Anniversary to U2’s eighth studio album Zooropa, originally released July 5, 1993.

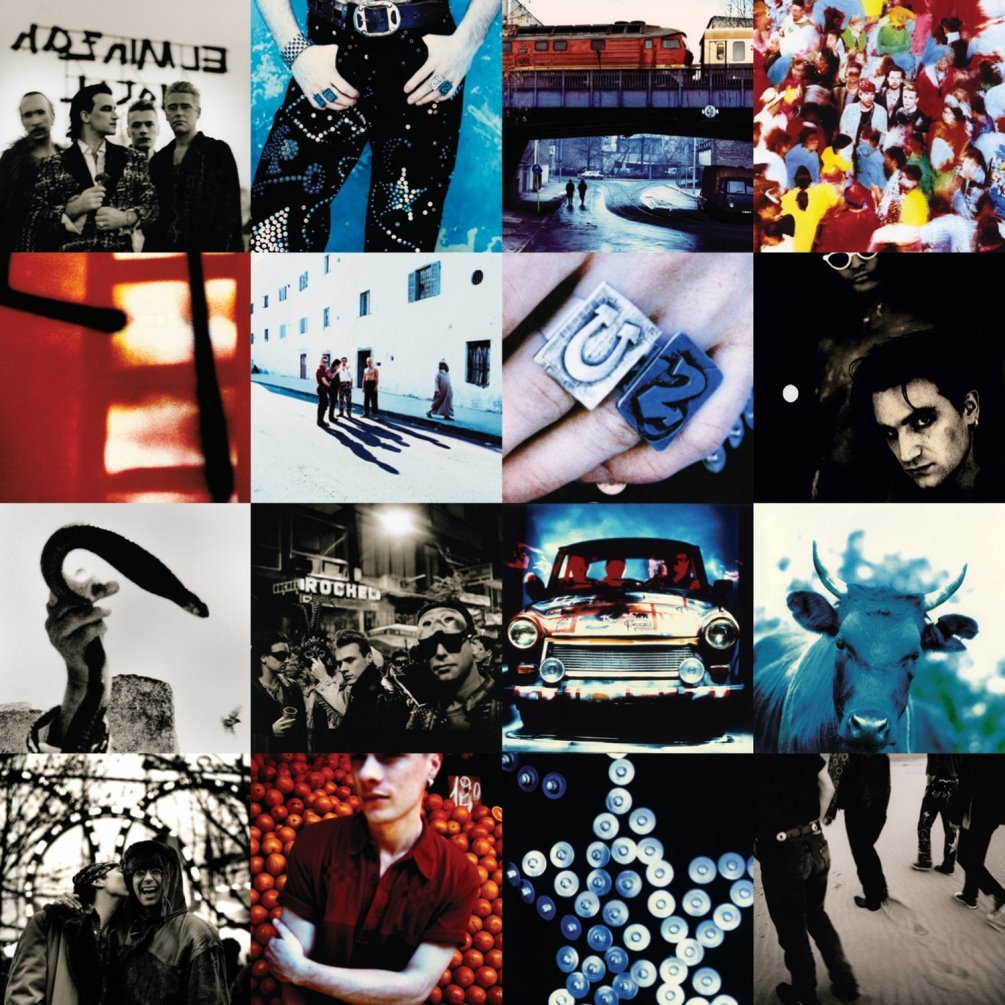

In February 1993, U2 were on a break before starting the second year of their massive Zoo TV Tour in support of their chart-topping 1991 album Achtung Baby. A commentary on media oversaturation, the tour featured massive TV screens and interactive multimedia that gave the audience a reality show-type experience, making the entire endeavor an insanely ambitious undertaking.

However, during the break, the band decided to go into the studio—just to record an EP, they told themselves. But then the ideas began to flow and, as the tour started back up in the spring, U2 decided to fly back and forth to Dublin to continue recording. The sublimely weird full album that came out of this mid-tour madness they christened Zooropa.

U2 viewed Zooropa as a low-key part two to Achtung Baby, making use of some of Achtung Baby’s leftover material, while writing other songs from scratch. Actually, Zooropa was low-key but also wildly experimental. Some songs referenced the Zoo TV Tour itself by using snatches of recorded soundchecks (engineer Robbie Adams created loops out of the interesting bits) and snippets from Zoo TV’s film collages. The whirring of a rewinding Walkman made it onto the album, and even Johnny Cash made a cameo. “If Achtung Baby was the first course, it was the perfect time to bring our audience something rather more experimental and esoteric,” explains U2 manager Paul McGuinness.

The Zoo TV Tour had become such a self-referential, meta circus of its own—with its TV assault on the senses and Bono portraying self-created characters like “The Fly” and the devil-horned “MacPhisto”—that it might have been easy to forget (if not for the Trabis used as lighting all over the stage) that “Zoo” initially referred to the famous Zoo stop on Berlin’s U-Bahn (subway). In 1990, U2 had begun recording Achtung Baby at Hansa Studios in Berlin, tapping into the city’s newly reunified status for the album’s political concept and its legacy of musical experimentation for its industrial-dance influences. “The idea of Berlin may have come from [producer Brian] Eno, because at one time [in the ’70s] Eno had lived in Berlin with David Bowie and Iggy Pop, the three of them in one squabblesome apartment in Kreuzberg,” recalls McGuinness.

A song called “Zoo Station” appeared as Achtung Baby’s opening track, but the station’s pop-culture relevance actually began long before in the ’70s and was captured in the cult 1981 film Christiane F: Wir Kinder Vom Bahnhof Zoo (featuring a soundtrack and performance by David Bowie), about real-life teenage heroin addicts who copped smack and sold their bodies out of Bahnhof Zoo. It was the Larry Clark’s Kids (or Euphoria) of its era, and it solidified ’70s Berlin’s reputation as a gritty mecca of sex, drugs, and underground rock-n-roll, while the Bahnhof became a tourist destination. “Zoo station and the idea of living in a zoo became a symbol of West Berlin, since West Berlin was surrounded by the Wall, much like a zoo,” notes Atlas Obscura. Though U2 weren’t glorifying hard drugs, Zooropa, at its heart, is an extension of this broader ’70s Berliner concept, including the whole of now-reunified Europe in the notion of a symbolic, chaotic, now-unleashed “zoo.”

I was living in Germany at the time of both albums, and the course of my own young life had followed Achtung Baby’s ’70s-to-’90s trajectory. Though they weren’t involved in any sort of heroin chic, in the ’70s my parents were twentysomething American hipsters living in Bowie’s Berlin. (“Everyone knew you didn’t go to Bahnhof Zoo late at night,” they said.) My dad had received a Fulbright and was teaching at the John F. Kennedy International School as part of his program. He brought my mom along, and I became a product of their adventure, arriving in the summer of ’77. So, to some extent, “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

Watch the Official Videos:

Our family had been living in Germany—now courtesy of the U.S. government in Heidelberg—well into the ’80s when the East Germans shocked the shit out of everyone and the Wall came tumbling down. As I began learning to drive as a teen in the early ’90s, it was still common to merge onto the Autobahn and see a Trabi trudging along as BMWs streaked past in a show of dominance. My German boyfriend Frankie even had a friend, Daniel, whose girlfriend was East German. “Ossi,” Frankie would call her in private, laughing at her naivete over whatever Western thing had escaped her knowledge on that particular day.

But I was ambivalent about Achtung Baby—even though I bought the album and played it from time to time, it felt like tourism, particularly in its opportunistic use of the Trabi as a symbol. I was living it, the fall of the Wall, so I probably figured (with a dose of teenage arrogance) that I didn’t need the experience reflected back to me in a big, bold, melodramatic way by a group of Irish rock stars. Zooropa, on the other hand, I had an immediate, psychotic love for.

It was its understatedness that hooked me. The video for Zooropa’s lead single “Numb” was everywhere in the summer of ’93, and although the NME eventually named it one of the “50 Worst Music Videos Ever,” I liked how strange and sparse it was, with the Edge looking straight at the viewer and singing in monotone without breaking eye contact. The video was a confrontation, a mirroring of the MTV viewer’s (your) own passive, numbed-out state. And unlike anything else “alternative” on American MTV (I first saw the video at my grandparents’ house in Minnesota), “Numb” had tinges of Kraftwerk and Euro-pop that made me feel at home.

I’d recently turned 16, which meant I could go out to bars and clubs in Germany, and I’d fallen in love with European dance music. I’d also begun to fall in love with the abundance of alternative music coming out of the United States; I appreciated its lack of slickness and rock-star pretension, and how playing it on my bedroom stereo felt intimate, like I was in conversation with the music rather than a passive listener. Despite U2’s reputation as a stadium band, Zooropa seemed to promise both—dance and introspective candor—and so late one morning after a night out, my friend Nikki and I rode the Strassenbahn into downtown Heidelberg, where I bought Zooropa at the local Kaufhof.

If Zooropa imagines reunified Europe as a zoo, U2 weren’t going to try too hard to define it. The opening track “Zooropa” begins cryptically yet appropriately with a German car metaphor—the Audi tagline Vorsprung durch Technik. “‘Vorsprung durch Technik’ became a motto for a nation that was putting the past behind it and restyling itself as a byword for quality, efficiency, progress and technology,” observes the Guardian. In the same way, U2 were using technology to sculpt a whole new sound, and maybe even an ethos, on Zooropa.

“It was our attempt to create a world rather than just songs and it’s a beautiful world,” Bono asserts. “The opening was our new manifesto, I have no compass, I have no maps, and I have no reason to go back. Brian Eno was in his element here. The studio became an instrument, a playground, lots of plastic attack from his DX7 keyboard.” (In this spirit of experimentation, “Zooropa” was the result of combining two separate pieces of music the band found while listening back to cassettes of Zoo TV Tour soundchecks. The two disparate elements fortuitously fit together, forming one song.)

From a group that had always come across as Type-A strivers, Zooropa is loose and beautifully moody, and focuses on nuance and vibe as opposed to hits. It also uses light humor to make its political points, as opposed to U2’s usual stridency. “Be all that you can be / Be a winner / Eat to get slimmer,” Bono sings, and we get the sense that post-Cold War Europe, succumbing to consumerist mania, isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

Reunified Europe was also experiencing a resurgence of fascism, spurred in part by the negative economic effects of East and West coming together. Germany’s population of Turkish immigrants were being terrorized by skinheads. In France, swastikas were scrawled on Jewish synagogues and community centers. And Jean-Marie Le Pen, leader of the far-right National Front, was getting worrying support. So in January 1993, Bono and the Edge traveled to Hamburg to join in on the Festival Against Racism at the Talia Theater.

In that light, “Numb,” while critiquing media oversaturation, also cautions against doing nothing, against allowing “media oversaturation” to serve as an excuse for not paying attention. “Don’t move / Don’t talk out of time / Don’t think / Don’t worry / Everything’s just fine / Just fine,” the Edge talk-raps over stuttering beats, soaring pop elements, the sound of a rewinding Walkman, and a sample of a Hitler Youth playing drums in Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will (the band had used it confrontationally in Zoo TV footage).

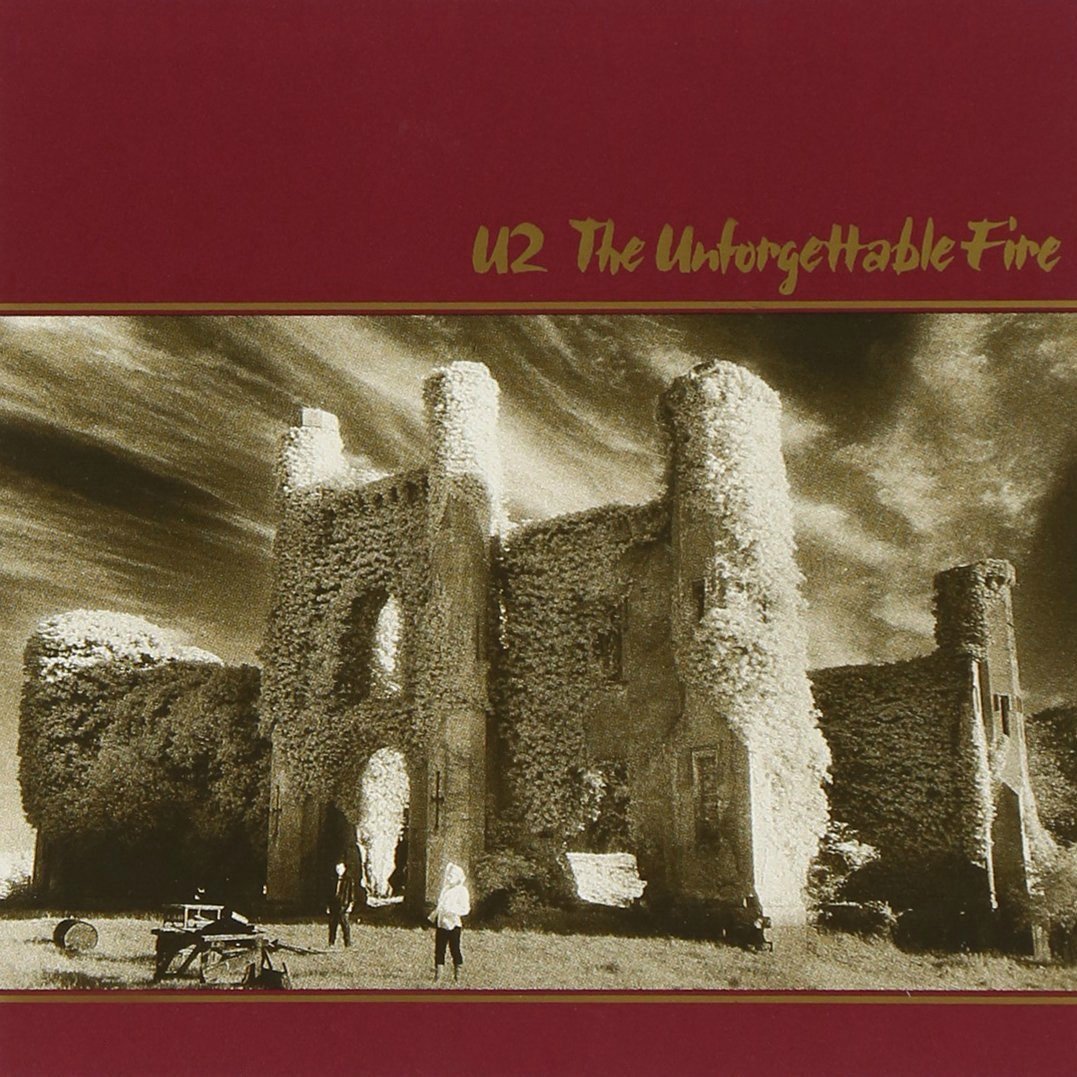

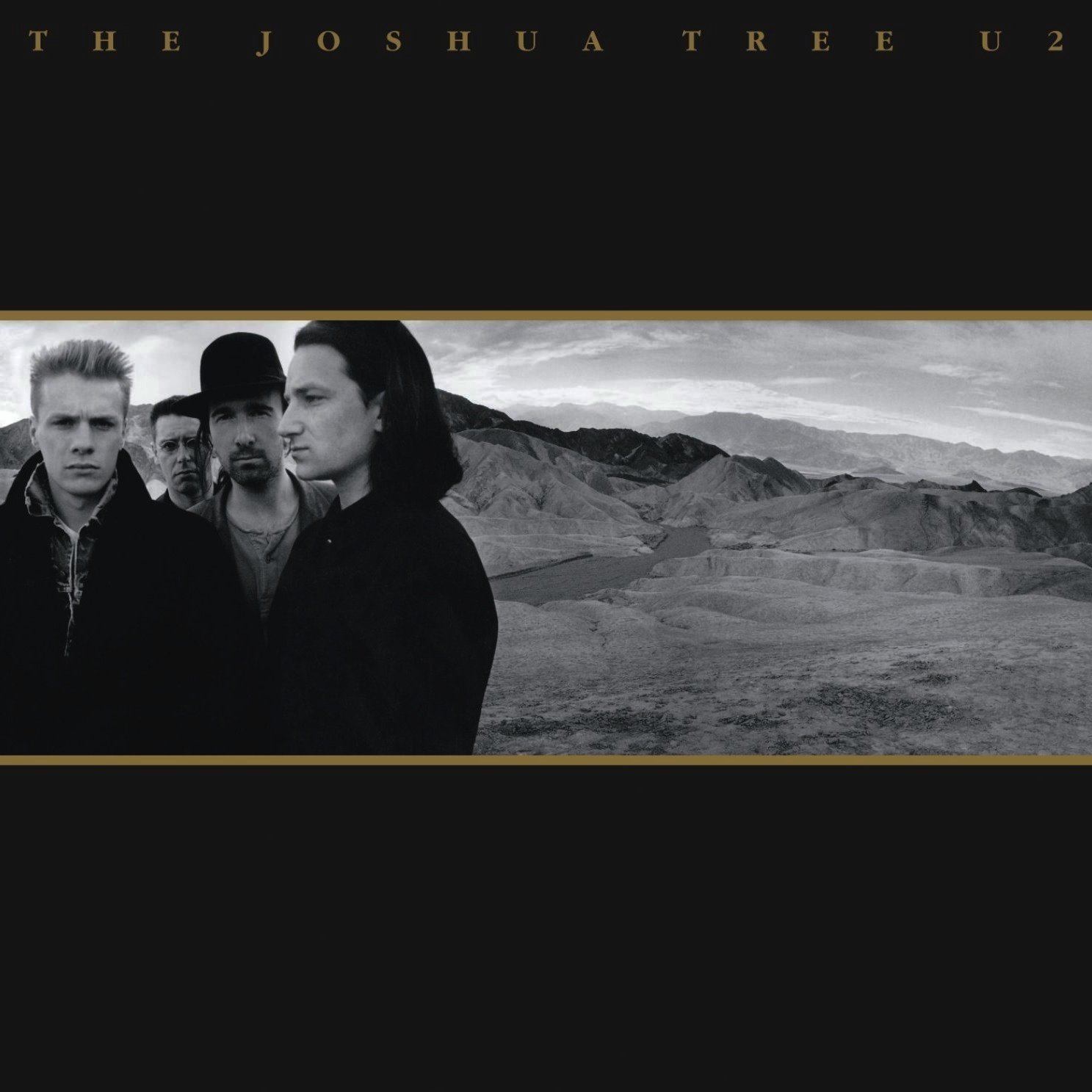

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about U2:

“[We were] really trying to ask the question of ourselves I suppose, as well as everyone else in Europe: ‘What do you want?’,” explains the Edge. “That seemed to be the question that kept coming back to us during the making of the album. Suddenly we were back on the road, touring in Germany, and the whole racist xenophobia issue exploded while we were there.”

Conversely, there are some incredibly romantic moments on Zooropa. Shimmery and wistful over tinkling toy piano, “Babyface” is a ’90s version of every prom song in every Molly Ringwald movie from the ’80s. The pulsing, zigzagging “Lemon,” one of my favorites that still makes my heart flutter like a teenager at the dance, is based on Bono’s having found Super 8 footage of his long-dead mother from when she was 24, looking lovely in a lemon-colored dress as a maid of honor at a wedding. The song comes across as an aching obsession for an object of lust, although knowing it’s about Bono’s mother doesn’t exactly ruin it. Bono also wove into the song empathy for the Edge, who had recently lost love and was raw from a divorce.

On both tracks, however, the romance comes at a remove—a man watches a woman on a screen, only fantasizing about touching her or interacting with her, much to his detriment. “And I feel like I’m slowly, slowly, slowly slipping under / And I feel like I’m holding on to nothing,” Bono wails with palpable loneliness and grief. Clearly, Zooropa was prescient in terms of Internet culture—social media, Zoom, chat rooms, limitless porn—and we’re all addicts circling our cages looking for the next anesthetizing fix. Midnight is where the day begins.

In the second year of the Zoo TV tour, U2 began using moments within their concerts to make unscripted satellite video calls to war-torn Sarajevo. On the night they played London’s Wembley Stadium, a group of Sarajevan women looked straight into the camera and confronted the concertgoers peering in on their plight: “You’re all having a good time. We’re not having a good time. You’re going to go back to a rock show. You’re going to forget that we even exist. And we’re all going to die.” The show never recovered.

If “Lemon” has a hint of the Oedipal, then “Daddy’s Gonna Pay For Your Crashed Car” has a serious Electra complex. It begins with a brass sample from the 1978 Soviet compilation Lenin’s Favorite Songs, but quickly begins pumping with industrial sex and swagger. We learn about a daughter’s codependent relationship with her father (it’s rumored to be a metaphor for heroin addiction), who gives her just enough independence that she believes she’s free, but really she’s in a prison— “Daddy won’t let you weep, daddy won’t let you ache / Daddy gives you as much as you can take,” Bono sings before orgasmically moaning Aha, sha-la. (When the Zoo TV tour hit Bologna, Bono as the devil MacPhisto phoned Alessandra Mussolini from the stage and left a message on her political party’s answering machine—“I just want to tell her she’s doing a wonderful job filling the old man’s shoes.”)

“Stay (Faraway, So Close!)” combines a leftover verse from Achtung Baby with some old-school piano chord progressions Bono had initially earmarked for a song for Frank Sinatra (they were pals). One of the more traditional U2 ballads on Zooropa, it furthers the theme of unbridgeable distance in a relationship. The song finally found its shape after German filmmaker Wim Wenders asked the band to write the theme to his film Faraway, So Close!, about angels who wish to live on Earth. Wenders ended up directing the song’s black-and-white music video in Berlin, which depicted the band as angels alongside footage from the film.

“Dirty Day” tackles the father-son dynamic and is based on a salty expression—“It’s a dirty day” —that Bono’s father used to say. Inspired by Charles Bukowski, a notorious drinker, the song sketches a portrait of a whiskey-soaked character who’s walked out on his family and, many years after, meets the son he’s abandoned. Bono first became a father around the release of Achtung Baby (the “baby” in the title took on personal symbolism) and so his deeper exploration of fatherhood on Zooropa speaks of someone with a young child still trying to find his bearings.

“The First Time” flips the “Dirty Day” script, imagining a prodigal son who returns only to decide he doesn’t want to hang around—“I left by the backdoor and I threw away the key.” It’s a song about losing one’s faith and, although U2 have never hidden their Christian leanings, it’s an ode to the atheists and agnostics. “I haven’t lost my faith but I’m very sympathetic to people who have the courage not to believe,” Bono said. Meaning, the uncertainty U2 embraced at the album’s beginning—I have no compass, I have no maps—has carried us all the way here in one piece.

Bono looked up to Johnny Cash as a father figure (they had collaborated before), and so he ceded the vocals on Zooropa’s final song, “The Wanderer,” to the Man In Black. Cash’s weather-worn voice fit perfectly with the song’s narrator, an Old Testament survivor—a cowboy walking “under an atomic sky”—who serves as an antidote to the album’s manifesto of uncertainty by choosing resolutely, as someone old and wise, to continue wandering into the unknown. “In other words, I don’t know but I accept this state of uncertainty,” Bono explains.

Zooropa ended up winning the GRAMMY award for Best Alternative Album in 1994, though Bono would balk at the “alternative” distinction, having hoped to win Album of the Year. “Yeah, alternative,” he said, rolling his eyes and holding the award that meant U2 had beat out R.E.M.’s Automatic For The People, Nirvana’s In Utero, Smashing Pumpkins’ Siamese Dream, and Belly’s Star.

But perhaps the highest praise came from David Bowie, who said of U2 to the Irish Times in 1993, “They might be all shamrocks and Deutsche marks to some, but I feel that they are one of the few rock bands even attempting to hint at a world which will continue past the next great wall.”

Listen: