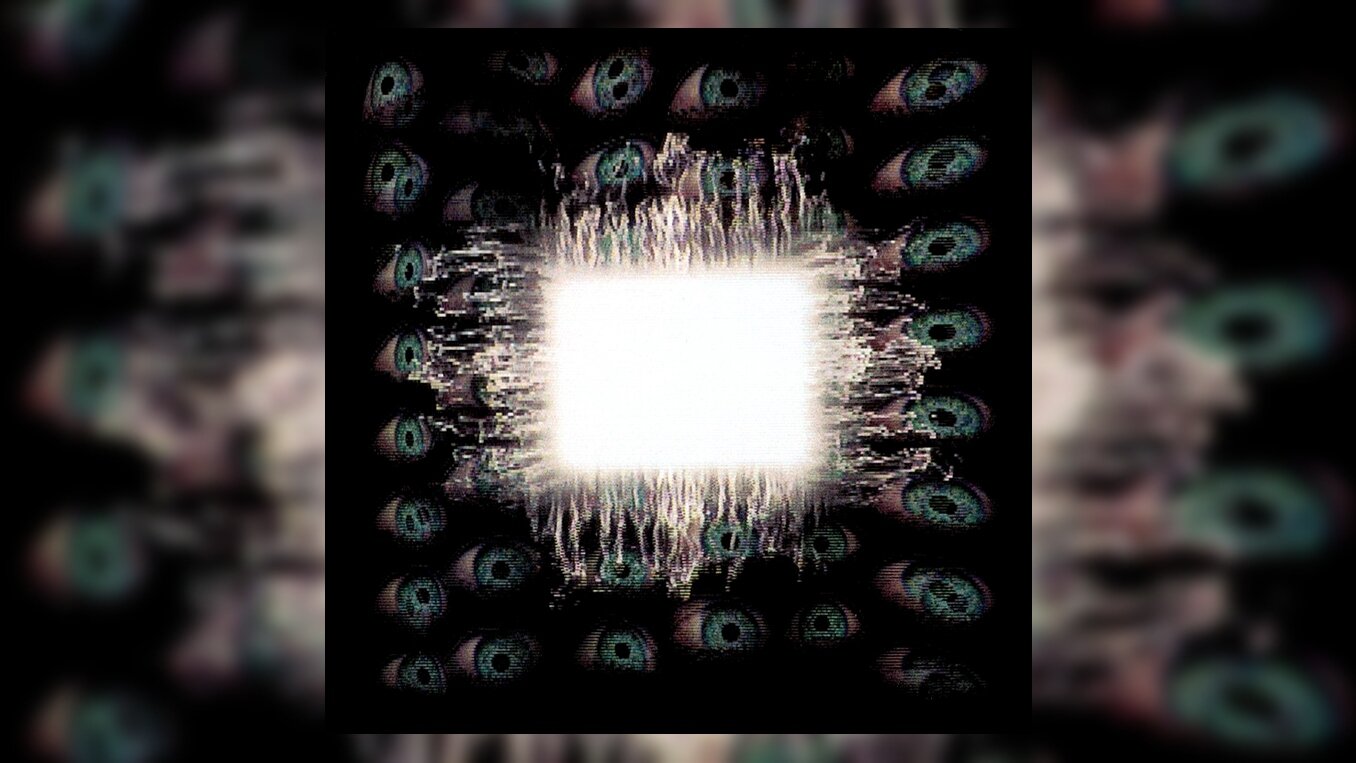

Happy 25th Anniversary to Tool’s second studio album Ænima, originally released September 17, 1996.

Frippertronics introduction. The push-and-pull of notes panning in every direction, looped to the delayed abstraction of infinity, sped up to create momentary euphoria in the midst of perpetual disorientation. “Stinkfist,” Tool’s opening descent into an album with cinematic and psychologically crippling themes throughout, provides the invocation with guitarist Adam Jones, drummer Danny Carey, and bassist Justin Chancellor like three continents converging at exactly the same time. Landlocked rhythms and riffs forged in the mind’s shadows. Drawing from Carl Jung, Freud’s pupil, and Bill Hicks, one of the world’s greatest stand-up comics, both would have been proud of Maynard James Keenan’s lyrical use of psychotrauma and dick jokes.

What transpires for the next hour and twenty minutes looks for comparisons where few exist. Ænima embraces the awful and the awfully funny. It embraces the shadows and the light. Most importantly it shimmers, scars and strikes at the heart of what makes individuals come together to discuss for hours on end the potential meaning of one verse while arguing the time signature of “H’s” coda during a single measure. For those alive during the album’s creation and the band’s ascent, each person could feel what it was like to be a fan of rock and roll’s other monoliths—Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath.

Certainly, there are moments that echo King Crimson. Other moments decry territory Pink Floyd once excavated. Greg Lake and Adrien Belew never possessed the flair for Keenan’s theatrical range. Geddy Lee’s elvish yawp exceeds Keenan’s range, but not his emotional delivery. Even Faith No More’s Mike Patton’s vocal gifts pale, and that is saying plenty. The instrument that is Keenan’s voice uniquely swells, quietly hushes, enthrallingly screams and melodiously croons when required. Therein lies the irony: his voice throughout Ænima is utilitarian wrapped in the despair of the characters he crafts with sheer beauty.

Fifteen perfect songs in one lifetime few bands accomplish. Fifteen perfect songs, intricately connected in the Nine Circles of Hell they illuminate, Tool accomplished in 1996. Bassist Justin Chancellor replaces Paul D’Amour by complementing his style, not reinventing it. David Bottrill, the Canadian producer who has worked with Fripp, Muse, Dream Theater and King Crimson’s welcomed return, Thrak, brings the band’s vision into fruition, taking nothing away from their compositions, focusing on the dynamics and precision. As an album, Ænima wastes not one second. Even the cleverly titled “Intermission” lasts for a minute, but remove the track from the album, and the narrative unfurls, losing its breadth of continuity.

In 1993, the band released a song about the double-edged blade of addiction and the creation of art. “Sober” became known just as much for its video as it was known for its powerful ode to a junky’s descent. The sonic aesthetics had been set with “Sober”: bass-centric focus and a rhythm section that transcended the standard bass/drummer relationship. All four members of the band supported each other. No one instrument felt more important than the other, except the bass.

The songs on Undertow, the band’s first full-length album released in 1993, hinted little at a follow-up as complex and merciless as Ænima. The Italian inquiry “Figlio di puttana, sai che tu sei un pezzo di merda?” begins “Message to Harry Manback,” a song that is more monologue than song, with little melody and devoid of feeling. The line translates as “Son of a bitch, do you know that you are a piece of shit?” Fans of the band and the song delved into realms that did not exist. As Keenan later explained, he invokes the spirit of the world’s greatest comedian, Bill Hicks, stealing the title from one of his jokes. His old friend from Rome named Francesco gets kicked out for stealing some things from Keenan when he stayed with him. The actual message fits the other, more serious messages, which curiously lead fans to believe that it continued the imagery of child abuse.

Because so much mystery surrounds the band, the perception of them ranges from humorless to monastic. Proceeding “Third Eye” is Hicks’ voice haunting us from the dead: "Today a young man on acid realized that all matter is merely energy condensed to a slow vibration. That we are all one consciousness experiencing itself subjectively. There is no such thing as death, life is only a dream, and we are the imagination of ourselves. Here's Tom with the weather."

The lyrics linger where the music erupts like a volcano with no warning. Yet, the harsh textures and somber moods established by the band masks the homage to Hicks while praising life’s illusory appearance. “I do not recognize the vessel / But the eyes seem so familiar” suggests a time when one existed before, an Eastern notion of the cyclical, non-linear lifetimes. The mystical appeals to the band, certainly. And Hicks’ role in the album is as a mentor, or a “Third Eye.” Kindred spirits, Keenan lives, and Hicks lived, outside society’s imaginary margins. The punchline, however, was not a dick joke, but how easily people can be duped into living a life they do not want.

People who knew Kurt Cobain and Ian Curtis said the same thing. Their depression came through the art they created. They laughed, joked around and found humor one of life’s best coping mechanisms. Another example of this is “Die Eier Von Satan,” which translates into the eggs or balls of Satan. Keenan lists the ingredients and instructions necessary to make some confection no one in their right mind would eat.

Was Ænima Tool’s Great Rock n’ Roll Swindle? Or is this the musical equivalent of James Joyce’s Ulysses? German, Italian, and low-brow English slang make for the perfect recipe of a sonic companion to the Irish author’s ode to his country of countless misfortunes. In moments here and there, sure. But the drama changes on a dime. “Pushit” follows the album’s court jester with high drama. “I will choke until I swallow... / Choke this infant here before me” juxtaposes the previous song’s silliness with eerie imagery of infanticide. The atonal intro echoes Stockhausen’s discordant motifs. The band locks into a 6/8 time signature. Keenan’s vocal effect blends with Jones’ distorted guitar track. Carey understates his playing in the beginning. Yet, nearly four minutes into the song, he showcases his hyperfocused attention to detail.

“Hooker with a Penis” reenacts a conversation between a fan of the band who believes that Tool has sold out. The album’s most violent moments bear the band’s bawdiest humor. Keenan meets a boy wearing a Beastie Boys t-shirt, Vans, nipple rings and tattoos. He accuses the singer of selling out, and Keenan tells the kid to look in the mirror, adorned with vintage ‘90s fashion staples, suggesting that he looks at himself and “point that finger up your ass.” The commentary is refreshing, because selling out was what many kids accused their favorite bands of once they broke big in the ‘90s. Keenan’s counter-argument to the kid underscores the irony of the kid’s accusations. The “dumb fuck” does not understand what it takes to make a record, and he was a “dip shit” for buying it after he sold his soul.

Despair and dick jokes make Ænima the juggernaut it remains today. The journey each musician takes the listener on resembles that of floating down the river Charon with two coins to give the ferryman. On the way, however, the metaphor of suffering and laughter during life’s long descent unveils the secret that Hicks and Jung rhapsodize over in their lives’ pursuit. A third eye emerges once suffering is recognized. Backwards masking Satan recipes and cursing Italians are the intermissions through which we get to laugh with each other. The rest is just abject misery and failure.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.