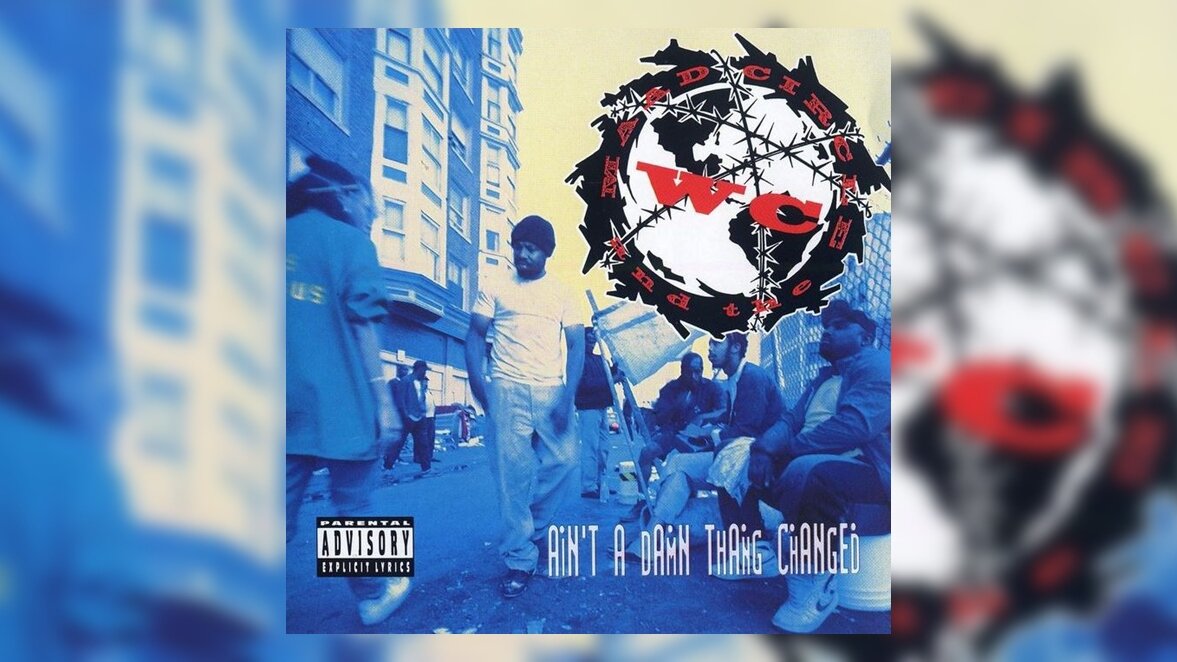

Happy 30th Anniversary to WC And The Maad Circle’s debut album Ain’t A Damn Thang Changed, originally released September 17, 1991.

What are the all-time greatest hip-hop albums about life in Los Angeles for young Black men before the 1992 L.A. Riots? N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton (1988) was the blueprint. Ice Cube’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted (1990) and Death Certificate (1991) are easy choices as well. DJ Quik’s Quik Is The Name (1991) is right there, along with Eazy-E’s Eazy-Duz-It (1988). King Tee’s Act A Fool (1988) and Compton’s Most Wanted’s Straight Checkin’ ’Em (1991) are underrated contenders. For all of its over the top cartoonish-ness, N.W.A’s second album Efil4zaggin (1991) deserves a mention. But right there in that upper echelon, just slightly below Straight Outta Compton and Ice Cube’s first two releases is WC And The Maad Circle’s 1991 debut album Ain’t A Damn Thang Changed.

William “WC” Calhoun, Jr. earned a good chunk of fame as a member of Westside Connection, the trio he formed with his comrades Ice Cube and Mack 10, but he’d been recording music as one half of Low Profile since the late ’80s. The group, made up of WC and west coast O.G./Rhyme Syndicate member DJ Aladdin, released the solid We’re In This Together LP in 1989, backed by acclaimed singles “Pay Ya Dues” and “Funky Song.” The group dissolved shortly thereafter, and WC then set about creating his new collective, the M.A.A.D. Circle (also more commonly stylized as the Maad Circle).

The M.A.A.D. (Minority Alliance of Anti-Discrimination) was comprised of WC and his brother/DJ Crazy Toones, as well as a rapper named Coolio. Coolio had made a little regional noise as a member of groups the Sound Master Crew and Nu-Skool, but was a relatively unknown entity among wider hip-hop audiences. The group’s production was handled by Sir Jinx and Chilly Chill of Da Lench Mob fame. The crew was rounded out by Big Gee, who, well, no one is quite sure what he did besides providing background vocals on a few tracks. The collective released their first album Ain’t A Damn Thang Changed three decades ago in the fall of 1991.

The album dropped in a particularly changed environment in Los Angeles. It was six months removed from the infamous Rodney King beating and the Latasha Harlins shooting. The CRASH special operations unit of the LAPD was still in operation, though not operating at its 1988 peak. Though gangsta rap was still the favored flavor for many record labels signing Southern Californian artists, gangsta rappers equipped with street knowledge were on the rise. Artists like Ice Cube, WC, and others began rhyming with a stronger political bent, preaching self-empowerment and community awareness, while still spinning cautionary tales of how to survive in the greater Los Angeles area. WC And The Maad Circle tackle these subjects with an arresting mix of grit, vivid storytelling, and often sharp humor, all of which coalesce to create street narratives that still sound applicable today.

WC sets the scene from the album’s intro, envisioning a world in the then-future of 1997, where “unemployment’s at an all-time high and living in L.A. is like Death Row: you’re bound to die. It’s nothing but modern day slavery, only they’ve changed from whips to billy-clubs.” Like many of their peers, the Maad Circle take aim at their public enemy #1: the LAPD. On “Behind Closed Doors,” WC and Coolio exchange stories of running afoul of the police.

WC leads off with “Dear Mr. Chief of Police, please excuse my handwriting / But try to understand that I wrote this with a broken hand / I’m just one of many in the inner city / Who’s been a victim of unseen police brutality.” He tells of getting pulled over by two officers and taking a beating for no reason. He remains stoic, however, “picturing my ancestors going through the same thing.” He then describes escaping and being pursued with “visions of Hitler chasing Jesse Owens,” before ending up in the hospital “with tubes connected to my lungs / just because your boys wanted to have some fun.”

Meanwhile, Coolio describes a former felon, back on the street after a five-year stint behind bars, running afoul of crooked cops. He boxes with an officer who tries to steal from him and wins, only to end up in the trunk of their patrol car before being dumped in the territory of a rival gang his neighborhood is feuding with. The details and flourishes the two add to each verse make their stories seem all that much more real.

On the album’s poignant first single “Dress Code,” WC and Coolio explain the deeper cultural implications of being judged by the way they dress. From the LAPD to school security to people in their neighborhood to the club bouncers, the pair decry those who judge them as thugs or drug dealers because of the pants, hats, or jewelry that they wear. WC raps, ”So what you're tellin’ me, is now I'm a crook / Who wrote the book on how a kid in my position's supposed to look?” and later promises, “And if I ever got a Grammy, man, I'd bail in some Chuck Taylors / to show the whole world it's alright to be yourself / Should I change the way I dress, so I can look like the rest?”

On “You Don’t Work, U Don’t Eat,” WC and Coolio are joined by MC Eiht and Da Lench Mob’s J-Dee (mostly known for gafflin’ at that point of his career). The four use the track to explore how hard it is to live on the straight and narrow, when you can make much more money through illegal means. WC explains how when you’re reduced to working at a “chicken stand now with the chicken with a spring at the top of my hat getting clowned,” buying a gun and robbing people doesn’t seem like such a bad alternative. Coolio later raps, “So jack I will, and go get some presidents / A foot in the ground and the other on an oil slick / Money ain't everything but neither is brokenness / Give me a knife cause I can't live off happiness.” MC Eiht brings the track home, stating, “I know it's wrong, but face it / A brother like me won't win the lottery / Ain't no faking when it's time to bring home the bacon.”

Four of the tracks on the album are WC solo cuts. Across all four, he flexes his unique storytelling ability to capture the reality of growing up in the concrete jungles of Los Angeles. Along with the small details, quite often WC adds touches of humor, which work well because, truthfully, WC is a pretty funny guy.

On “Out On Furlough,” he describes being in the wrong place at the wrong time and getting sent back to prison for violating his parole. He frames the story by talking about going to a party, winning money at dominoes, and rolling to the store with a guy named Joe, “who wore a golf hat with a big-ass afro.” On “Caught In A Fad,” WC criticizes rappers and friends who embrace false identities instead of remaining true to themselves. With the first verses, he promises to never sell out his musical credibility unlike those “wearing flowered shirts and flat-tops on their album covers.” He uses the second verse to excoriate a phony, self-proclaimed enlightened individual, who hypocritically claims to be vegetarian, but “who weighs 380 off of fruits and berries” and sells crack during the day but “carries a sword and wears dashikis at night.”

WC also tackles the struggles of growing up in a broken home on the aptly-titled “Fuck My Daddy.” It features WC at his angriest, firing off unfiltered rage towards the man who abandoned him, his brother, and his mother at a young age when they were all in need. The lyrics echo long-held pain and fury towards the man, with lines like: “I used to hide under the covers with my eyes closed / Cryin’ and hopin’ tonight that daddy didn't trip / ’Cause momma already need stitches in her top lip / Cause daddy got mad and beat the hell out of her / And throwin’ chairs against the wall every night, became a regular / I used to pray and hope that daddy would die / Cause over nothin’ momma's sufferin’ a swoll up black eye.”

Though “Fuck My Daddy” showcases the album at its bleakest, not everything on Ain’t A Damn Thing Changed is that emotionally charged. The crew is also good at just cutting loose and kicking some regular, no-nonsense emcee shit. WC and Coolio shine on “Get On Up That Funk,” trading rhymes back and forth about how funky music cures all your ills. Coolio testifies, “Whenever I'm feelin’ bad, angry or upset / I grab a cassette, and pop it in the tape deck / Album or 8-track, as long as it ain't wack / Funk is addictive, but not like crack, Black.”

The album’s title track serves as WC and Coolio’s statement of how they each work to keep their heads straight in the face of growing notoriety. With “Back To The Underground,” the album’s closing track, the pair set forth a lyrical explosion, trading verses, rhymes, and lines back and forth with the best of them, all while proclaiming that rappers should avoid compromising their principles in the pursuit of fame.

After the release of Ain’t A Damn Thing Changed, fame came calling for both emcees, albeit through different means. In 1994, Coolio released his debut solo album It Takes A Thief through Tommy Boy Records, and enjoyed massive commercial success. “Fantastic Voyage” became a ubiquitous hit, and the album went platinum. He followed it up with Gangsta’s Paradise a year later, and the album went double platinum. The title track is one of the most successful rap singles of all time, and won a GRAMMY awards for Best Rap Single. Somewhere in between, Coolio left the Maad Circle amicably.

WC kept the Maad Circle together for another album, holding strong through the departure of Coolio, Sir Jinx, and Chilly Chill. He released the underappreciated Curb Servin’ in 1995, featuring the indelible west coast anthem “West Up!” featuring his Westside Connection brethren Ice Cube and Mack 10. The trio earned considerable success beginning with their 1996 debut album Bow Down. WC released a few solo albums afterwards, with varying results, but all still utilizing his unique narrative ability and penchant for humor. He frequently tours with Ice Cube, acting as his hype-man. Sadly, Crazy Toones passed in early 2017 due to a heart attack. He DJed for Cube for years and continued to put out mixtapes on his own.

WC And The Maad Circle’s legacy has endured. The title of Kendrick Lamar’s breakout album good kid, m.A.A.d city (2012) is an indirect homage to the group’s original acronym, and listening to Lamar’s music, you can hear the same mix of striking storytelling, tragedy, and humor added to the mix. Ain’t A Damn Thing Changed may not be the best-known or most acclaimed album of hip-hop’s golden era, but its relevance and impact endure thirty years later.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.